The Americans truly feared in December that the troops of the Warsaw Pact would enter the Polish People’s Republic. The announcement was not, however, about December 1981, when Gen. Jaruzelski imposed the martial law, but about December 1980 - only three months after the Solidarity Movement was born. In November, democratic candidate Jimmy Carter lost the presidential elections in the United States. Nevertheless, it was his administration which ruled in the White House until January 1981. Did Carter really stop one of the biggest crises in the history of the Cold War before handing over the reins to Ronald Reagan?

“A critical phase”

In the beginning of December 1980, as a reaction to the troubling movements of Russian troops near the border with Poland, Washington began an unprecedented campaign of publicising Moscow’s offensive plans. The then advisor to Carter, Zbigniew Brzeziński, recalled that during these December days the American-Soviet relations entered “a critical phase”.

On December 2nd, the CIA wrote a special report, the so-called alert memorandum, pointing to the clear deterioration of “the Polish crisis” and the growing pressure on the Polish People’s Republic from Moscow. At the same time, through diplomatic channels, Carter warned the European leaders and even the governments of China and India about the possible intervention of the USSR. On the following day, the outgoing president pointed to:

“An unprecedented gathering of Soviet troops along the Polish border.”

Also on December 3rd, through a special hotline (a special communication channel between the White House and the Kremlin), Carter warned Leonid Brezhnev that an eventual military intervention in Poland would seriously damage the American-Soviet relations. He underlined that Poles should resolve their issues on their own.

Publicising Moscow’s plans

Not long after, in a public speech, president Carter expressed his growing concern regarding the mobilisation of troops. They were not radical statements by any means, but the president clearly wished to manifest left and right not only his concern but also Moscow’s plans.

Still on December 3rd, the CIA once again informed about “very unusual or unprecedented at this time of the year” movements of Soviet troops. On December 4th, Col. Kukliński, the famous “atomic spy” for the CIA in the General Staff of the Polish People’s Army, sent a very urgent note in which he described the detailed plans for an invasion and warned that it would take place in the following four days. It is not surprising then that since that moment the White House worked day and night and called a meeting after a meeting. Even president-elect Ronald Reagan was invited to these talks.

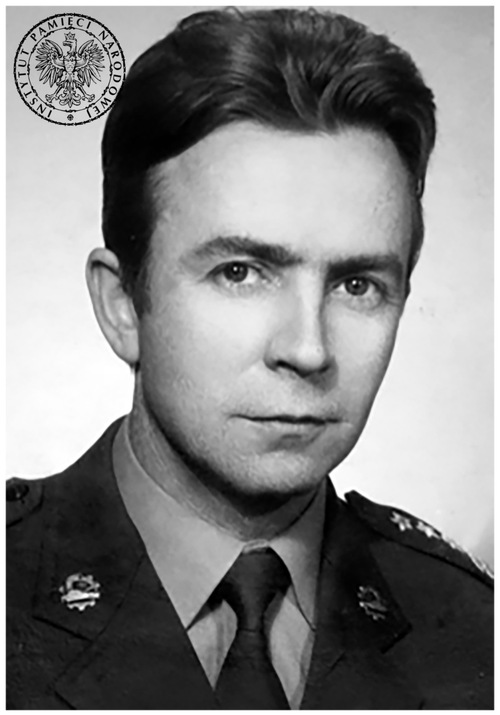

Portrait photo of Colonel Ryszard Kukliński. Digital copies of the photo and other documentation regarding Col. Ryszard Kukliński were handed to the Archives of the Institute of National Remembrance by the CIA

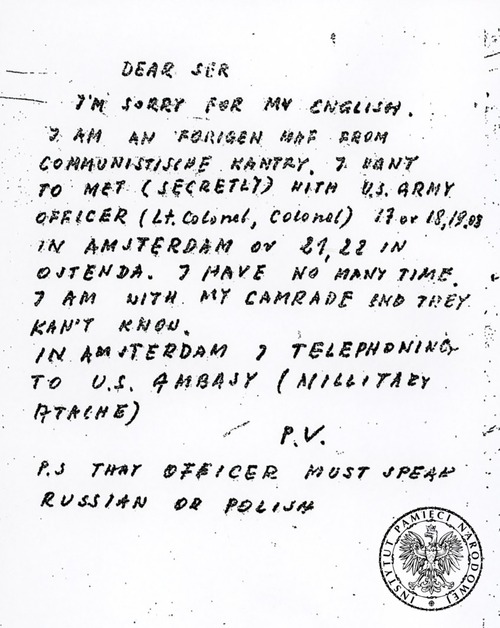

A letter in which Col. Ryszard Kukliński established contact with the American side. The letter was signed P.V. which meant Poland Victory/Polish Viking. The letter was written with poor English. This style was to protect Kukliński from being discovered as a spy. Digital copies of the photo and other documentation regarding Col. Ryszard Kukliński were handed to the Archives of the Institute of National Remembrance by the CIA. Author: Ryszard Kukliński. Wilhelmshaven, August 11, 1972

In the next report of the CIA, made on December 5th, there was an information that in the following three days 15 Soviet divisions would enter Poland under the guise of military manoeuvres. Before that deadline, on December 7th, Carter sent another firm (and publicised) warning to Brezhnev, although not threatening with the use of force but a complete freezing of bilateral relations. What is important, American troops were not put on high alert during that time. It was feared that too much readiness could only speed up the Soviet attack and make it inevitable. It shows that publicising Moscow’s plans was not strictly a confrontational tactic. Hence, it is difficult to agree with the analyses of the Security Service of the Polish People’s Republic of that time which assumed that the American authorities used the “anti-Soviet campaign” in diplomacy and media to lead to an actual invasion. It was to be allegedly favourable to them as a pretext for taking on a harsher political approach towards the eastern bloc.

Diplomatic cooperation of the West

On the same day of December 7th, 1980, the American administration, along with the European capitals, (with a series of telegrams) hastily prepared a unified approach in case the invasion scenario came true: an attack was to be met with a complete breaking off of diplomatic relations with Moscow, a trade embargo and an end to the demilitarisation talks. There was no mention of any military activities, although the idea of blocking Cuba as a response to the Soviet operation was banded around. Possibilities of real actions were limited - no one intended to “die for Gdańsk”. Nevertheless, the declarations of the West’s unity in the face of the USSR’s actions were just as important, even if they were quite vague.

The Americans also remained active when it came to the North Atlantic Alliance. Still on December 7th, 1980, US ambassador to NATO William Tapley Bennett sent a statement from the White House to the Alliance’s Secretary-General, Joseph Luns, in which president Carter once again emphasized:

“It seems that the preparations for a possible Soviet intervention in Poland have ended.”

Additionally, the American leader wrote:

“We acquired evidence that the Soviet Union has made the decision to enter Poland.”

He also proposed considering - only considering - introducing a heightened state of combat readiness of the Alliance’s troops. Although he underlined that there was no certainty, he stated that:

“The probability is so high that Western countries should take all the necessary steps to influence the decision-making process of the USSR.”

On December 9th, an extraordinary meeting of NATO officials took place during which a special scenario was worked out in case of an invasion. It was established that in the case of an attack military budgets would be increased, all western ports closed to the Russians, ambassadors recalled from Moscow and the talks under the Conference for Security and Cooperation in Europe (CSCE) boycotted. Unspecified economic sanctions on the USSR and the Polish People’s Republic were also envisaged. And even though the allies agreed that they needed to be implemented, they disagreed on the level of specific sanctions “for there and then”. West Germany remained reluctant in imposing harsher sanctions on Moscow.

In this context, on December 11th, the North Atlantic Alliance only formulated a vague note where it stated that the recent Soviet moves “seriously endangered” the international political climate. “Poland alone should decide on its future” - it was added.

The Americans also included the Vatican and the Solidarity Movement in its diplomatic campaign. During these days Zbigniew Brzeziński held a short conversation with Pope John Paul II. He tried to use his Vatican channels to warn the leaders of the Solidarity Movement about the attack. At the same time, the report of the American president for the Congress Commission on CSCE Affairs, informed about the harsh attacks on Jacek Kuroń, the Workers’ Defence Committee and Confederation of Independent Poland. The US State Department also strongly advised individual American citizens against visiting Poland.

The wait

Meanwhile, time passed and the invasion was not happening. The CIA began underlining the difficulties of predicting an exact date of the invasion due to bad weather over Poland which made it impossible for surveillance satellites to acquire useful data. This only added to the seriousness of the memorandum prepared for president Carter by Zbigniew Brzeziński on December 12th, when he analysed the course of the sudden summit of the Warsaw Pact from a week earlier and warned:

“The intervention is ready, but the final decision might not have been made yet, so we may still have a chance to put a stop to it.”

***

In the following days, the tensions visibly decreased. On December 19th, Brzeziński informed Carter that, according to the CIA reports, the Kremlin decided to postpone the attack to an unspecified date somewhere in the future. He emphasized that this decision was caused by “the effectiveness of the western counter-propaganda campaign”, implicating the USSR’s fear of political and economic backlash. He later repeated that thesis in his memoirs. Did the Americans truly stop Moscow’s ambitions by their publicising campaign of diplomacy and media coverage?

This was undoubtedly their goal. The various initiatives in an alarming tone were aimed at depriving the Russians of the element of surprise. They were to show that the democratic world had been watching Brezhnev’s every move and agreed to adopt a unified approach, not a radical one but (seemingly?) uniform. All of this could be read as a countermeasure, placing the potential aggressor in an uncomfortable position, somewhat forcing him to choose another option than the one publicised by the political opponent. This manoeuvre required subtlety as overacting posed a threat of achieving an opposite effect: an actual offensive of the USSR.

***

Finding analogies between the past and the present is quite a risky process, however, it is difficult not to observe the similarities, at least on a surface level, in the political approach of the United States of America towards Moscow in December 1980 and February 2022. Warnings about an imminent invasion, alarming headlines in the media, dramatic statements by the administration, consultations with the allies, the peculiar role of Germany - all of this with limited military involvement and suggestions of no radical actions in case of an attack. These elements build a small bridge between the past and present crises.

Can the strategy of “deterrence through publicising” be successful? In 1980, the Americans were able to proudly say yes, although it is impossible to prove without doubt. We shall see if this strategy proves to be successful in 2022.

The Institute of National Remembrance created a unique animated short presenting the Martial Law period in a whole new light – not another gloom-and-lost-hope story but a narrative about unfaltering struggle and resistance, which in the long run allowed Poles to defeat Communism