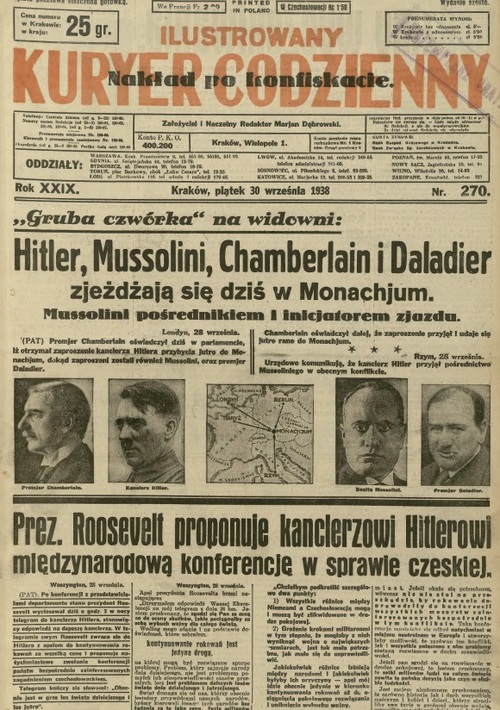

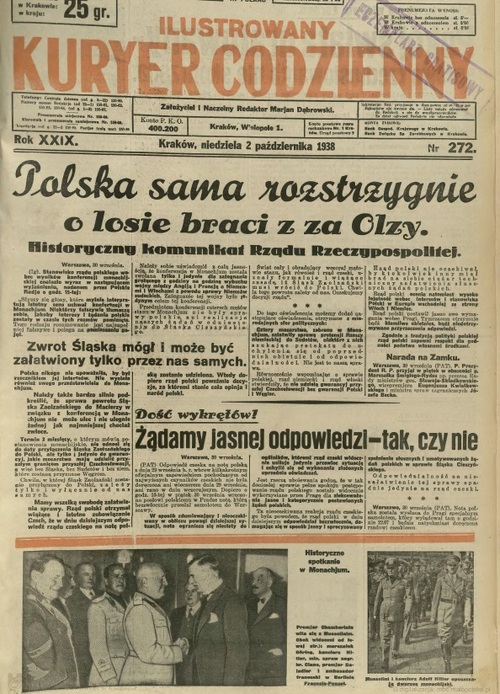

The accusation of Poland’s participation in the partition of Czechoslovakia in autumn 1938 was one of the key elements of the historical propaganda aimed at the country by Hitler’s Germany. The decision on the division of the territory of the first Czechoslovakian Republic was made on September 29th during a conference in Munich, with the silent approval of France, Great Britain and Italy. The democratic states remained passive in the face of Hitler’s demands. The final shape of the new borders was to be established by the commission consisting of representatives of the states present at the Munich conference and the Czechoslovakian Republic. The participants of the conference also published an additional statement to the treaty which considered the Polish and Hungarian minorities in Czechoslovakia. When compromise was unreachable on these matters after three months, another meeting of the Munich four was announced.

Photocopy of the photography of the signing of the Munich Agreement 29-30 IX 1938 In the first row from the left are Neville Chamberlain, Edouard Daladier, Adolph Hitler, Benito Mussolini, Galeazzo Ciano. Photo: AIPN

A critical review of the Polish policy during the Czechoslovakian crisis (omitting France’s responsibility for the course of the events) was included i.e. in the book by the then ambassador of France in Warsaw Leon Noël. See German Aggression on Poland, Warsaw 1966 (first edition – Paris 1946). In the picture the diplomat is in an official dress suit, in 1935. Photo: NAC

“Nothing about us without us”

The Polish diplomacy presented its stance in the case of the decisions made at the conference, after they had been publicly announced, stressing that it did not find them binding and that it followed the rule “nothing about us without us”. Warsaw feared that the world powers could – just like they did with Czechoslovakia – make a pact with Germany at the expense of the Republic of Poland, making it a pawn in a diplomatic game. Given the political situation at the time, the threat of “Munich solutions” being used on Gdańsk, Polish Pomorze and Silesia regions was real.

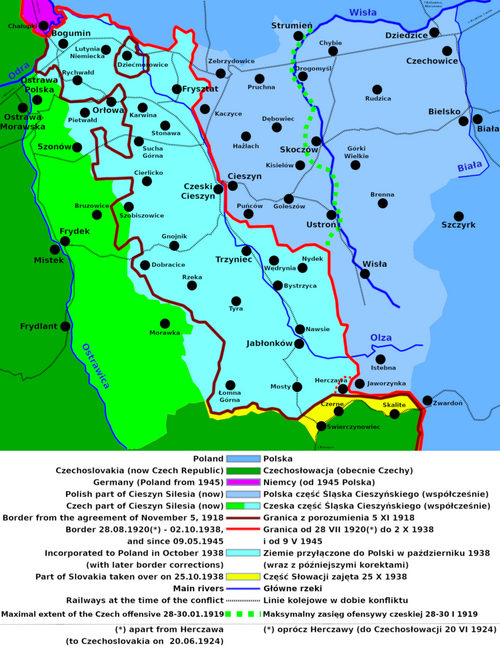

As a result, on September 30th 1938 Poland presented an ultimatum to Prague demanding the inclusion of the Cieszyn and Frysztat regions to Poland within ten days, organisation of a plebiscite at the remaining Czechoslovakian Republic, where many Poles lived, and freeing all political prisoners of Polish origin. On October 1st all the demands were met and the Czechoslovakian authorities emphasized their good will in their attempts to de-escalate the conflict.

The indifference of world powers

The reflections on the possibility of Poland standing in Czechoslovakia’s defence are purely speculative. There is no doubt that the indifference of the major world powers and their intention to put the political and moral responsibility on Poland determined the course of action of its authorities. For Poland the idea of sending troops to defend its southern neighbour was out of the question. Given the international situation at the time, such operation was doomed to fail from the beginning and the Republic of Poland would be fighting the Third Reich on its own, since Paris and London were not ready for war and were both focusing on the appeasement policy. It would be fully justified to state that in the case of an armed conflict between Germany and France, Poland would actively support the latter if only it showed the will to fulfil its promises to the allied Prague. Thus, the responsibility for the statehood crisis of Czechoslovakia lies with France and Great Britain, whose diplomatic representatives many times forced the Czechoslovakian authorities to make more and more concessions to Germany in 1938.

Participants of the conference of the four world powers in Munich after the debates had ended. In the picture, standing at the airport, from the left: the German secretary of state in Auswärtiges, Amt Ernst von Weizsäcker; the British ambassador to Germany, Neville Henderson; the Italian ambassador to Germany, Bernardo Attolico; the French ambassador to Germany, André François-Poncet. September 29-30 1938 Photo: NAC

Poland never initiated any actions contributing to the territorial disintegration of the country of Czechs and Slovaks. Also the Polish minority, gathered near the Polish-Czechoslovakian border (mainly Cieszyn Silesia), repressed for years, was not the main reason behind the crises of Czechoslovakian statehood. Poles living at the Czechoslovakian Republic based their postulates on the programs of other minorities living there, so they surely could not have been a factor equal to the role the Germans living in the Sudety mountains played.

In the face of Germany’s expansion and Soviets’ demonstration

The relations between Poland and Czechoslovakia cannot be dissected without including Germany’s role in Europe. Today, historians reject the thesis on the alleged secret Polish-German agreement on Czechoslovakia, which was often mentioned in the historiography of the communist Polish People’s Republic following the example of Soviet researchers. Moreover, the entry of the Polish troops to the Zaolzie region could be interpreted as an anti-German move aiming to not only emphasize the political position of Poland, but also to secure an economically strategic terrritory. The proof of the lack of complicity between Warsaw and Berlin was the disagreement on the town of Bogumin.

Poland would actively support France if only it showed the will to fulfil its promises to the allied Prague.

It was also clear that the demonstrative offer made by the Soviets to send troops to aid Czechoslovakia, based on the treaty of mutual help made between Prague and Moscow in 1935, had no chance of being realised. Such actions were only possible if France engaged its army in the defence of the Czechoslovakian Republic, which was never even considered by its leaders, as proven above. Therefore, the fact Poland did not allow the Red Army to pass through it was not the reason behind the lack of aid from the Soviet Union. The offer made by the USSR was nothing but propaganda aiming to strengthen the picture of the communist empire as the determined “defender of peace”, while the threat of breaking the non-aggression pact with Poland from 1932 was part of the show of force policy.

* * *

The events from autumn of 1938 must be analysed in the context of the events prior – they were the consequence of difficult two-way relations between Poland and Czechoslovakia during their existence on the political map of Europe since 1918. The Republic of Poland entered the territories taken by the Republic of Czechoslovakia in 1919 and accepted by world powers in the summer of 1920, when Poles were in the middle of their decisive war with the Bolsheviks. Additionally, Poland made its demands only when the Czechoslovakian authorities, lacking the will and means to defend the territorial integrity of its own state, surrendered to the dictate of world powers. It was clear that the Czechoslovakian Republic lost its status of an independent entity of international politics, which was further proved by the events of March 1939, namely the final fall of Czechoslovakia.

The decision to take the Zaolzie region, treated as a realisation of the well-founded Polish postulates, was without doubt one of the toughest choices made by the people in charge of the foreign policies of the Second Republic of Poland.