It is the result of i.e. a touching book about Bornstein by Arnold Mostowicz (Ballad of Blind Max), the largely successful theatre play (Kokolobolo, or the story of adventures of Blind Max and Shaya Magnat) and even a city game (Catch a thief). However, from the historical perspective, based on recovered archives, Bornstein was first and foremost the main hero of one of the greatest scandals of the Łódź State Police prior to the war. The background of the scandal were the accusations of corruption and compromising relations between the officers of the law and the Łódź gangsters. Its finale, definitely put an end to the criminal career of “Blind Max”.

“Brotherly Help”

The incident, which later caused the series of unfortunate events, took place in autumn 1929. On September 19th, in front of the infamous brewery “Kokolewole” on the corner of Pomorska and Wschodnia streets in Łódź, a 42-year-old Jew Srul Balberman was shot - a member of the Jewish association “Brotherly Help” operating since 1928. The organisation’s official goal was to bring aid to the poor Jewish population, among other things, gathering funds for the dowries of poor girls. In reality, the charitable association was nothing but a front for the activities of the arbitrament, commonly referred to as Din Torah. The court was to rule on disputes between Jews, but it actually operated as a regular criminal organisation. Its members were feared by the Jewish population – they enforced punishments, extorted payments, performed blackmail and took money for protection. One such Din Torah was led by Menahem Bornstein, a thief and a crook, due to his visible eyesight defect called “Blind Max” by the residents of the Bałuty district of Łódź. It was him who mortally shot Balberman, thus getting rid of a dangerous opponent in the criminal group.

The investigation of the murder was conducted by the Investigative Department of the State Police of the city of Łódź, led by senior commissionaire Stanisław Weyer – an officer of German origin who served in the Łódź State Police since November 1918.

The charitable association was nothing but a front for the activities of the arbitrament, commonly referred to as Din Torah. The court was to rule on disputes between Jews, but it actually operated as a regular criminal organisation. Its members were feared by the Jewish population – they enforced punishments, extorted payments, performed blackmail and took money for protection.

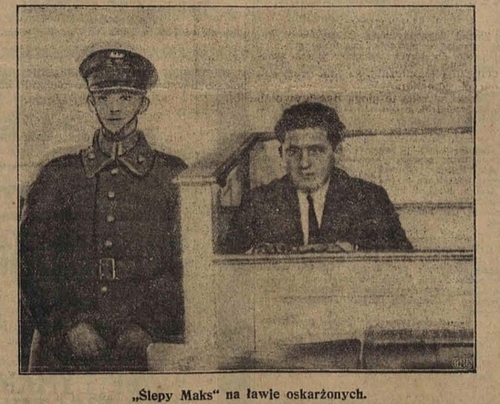

Bornstein, accused of murder, stood before the Regional Court on January 15th 1930. His trial aroused an enormous interest of the citizens who gathered in front of the court’s building to catch a glimpse of the most infamous criminal in Łódź. The sensational trial ended with an even more sensational verdict, which was a bitter defeat for the law enforcement and prosecution. The court, after questioning several dozen witnesses, on January 16th acquitted Bornstein from the murder charge, ruling that he was acting in self-defence.

While the Jews took care of their matters discretely, among their own, the Police turned a blind eye. However, the so-called “Blind Max” scandal, meticulously described in the Łódź press, became a public matter. That is why, the spectacular acquitting of Bornstein began weighing heavily on the Łódź Police, especially on the senior commissionaire Weyer responsible for the case.

Office of chief Nosek

The case became even more complicated when in January 1931 Bornstein, wanting to completely separate himself from the “Brotherly Help” compromised during his trial, created an office of applications and requests in Łódź called “Defence”. Apart from a few typists, a secretary and a lawyer, its most important employees were several, well-built men whose only job was an efficient resolving of “requests” sent to the office. Not flattering for the Łódź administration was the fact that said office was registered by an illiterate.

The arrogance and confidence of Bornstein – “the king of the Bałuty district”, must have irritated Weyer greatly. What is more, the gangster did not bother to hide his acquaintance with a certain high-ranking officer – the chief of the Investigative Office of the Province Police – deputy inspector Zygmunt Nosek who was Weyer’s superior. “Blind Max” ostentatiously spend time in his office and more and more rumours surfaced about them drinking together in various pubs in Łódź. Weyer pointed out to Nosek that his close relations with the gangster are shaming the police uniform, but he dismissed his words claiming that Bornstein was his confidential informer.

A conflict began slowly brewing up between the province investigative office of deputy inspector Nosek and the Łódź investigative department led by senior commissionaire Weyer. When in August 1931 Weyer filed a motion to the Łódź governor to take back the permit for the activities of Bornstein’s office, chief Nosek immediately intervened with the chief-of-police of the city of Łódź, deputy inspector Anatoliusz Elzesser-Niedzielski. However, the chief took the side of his subordinate and the controversial office was finally closed. The official reason behind this decision was Bornstein’s illiteracy.

I am kindly reporting…

In the city’s police department a decision was made to tighten the actions against the group of “Blind Max”. More and more inspections of the gangster controlled pubs were conducted, illegal casinos were taken down in several cafes in Łódź. The successes of the Investigative Department in the fight against the Łódź underworld quickly brought unpleasant consequences for Weyer. In November 1933, anonymous message were sent to the province chief-of-police in which Weyer was accused of, among other things, taking bribes.

The content of the denunciations was meticulously analysed and tested in graphology. Bornstein quickly wound up on the list of suspects who might had sent the anonymous messages, while deputy inspector Nosek was suspected of talking him into it. A huge scandal was on the horizon for the Łódź Police, so the results of the preliminary investigation were immediately sent to the Police Headquarters in Warsaw. Already next month, Nosek was transferred to Lviv to the same position. Weyer in turn handed a special report with explanations for his supposed bribery in December 1933 and demanded an investigation into his actions to be launched which, after a few months, was discontinued.

“Blind Max” in court again

After Weyer gathered sufficient materials incriminating Bornstein the case, in the beginning of 1934, was given to the Regional Prosecution in Łódź. On February 21st 1934 police officers, led by senior commissionaire Weyer, arrested Bornstein in his home.

On February 21st 1934 police officers, led by senior commissionaire Weyer, arrested Bornstein in his home. During the search of the house they secured evidence which, apart from the criminal activities of “Blind Max”, proved his relations with deputy inspector Nosek.

During the search of the house they secured evidence which, apart from the criminal activities of “Blind Max”, proved his relations with deputy inspector Nosek (i.e. business cards of the chief of the Investigative Office and a blank cheque for a hundred zloty signed by him).

The second trial of Bornstein before the Regional Court in Łódź began on May 6th and lasted until May 13th1935. The indictment counted 59 pages, and the case materials 1100 pages. 126 witnesses testified. The special envoy of the Headquarters of the State Police in Warsaw also carefully observed the course of the trial. Bornstein was accused of 18 criminal acts – various kinds of fraud, blackmail, extortion and punishable threats. Apart from him, merchant Henoch Fuchs – a member of the “Brotherly Help” and Hersh Grunis – Bornstein’s secretary sat in the dock. The former colluded with “Blind Max” on extortions and the latter wrote the anonymous messages defaming commissionaire Weyer.

The verdict was announced on May 17th 1935. Bornstein’s convoluted explanations, even simulating mental illness, did not help him. The Regional Court in Łódź sentenced him to six years in prison, sparing one year on the basis of an amnesty and including a year and a half he spent in police custody. The second accused – Fuchs – got a year and three months of imprisonment, and Grunis was sentenced for eight months in prison.

Bornstein served his sentence in a prison in Piotrków Trybunalski. In the repertory for year 1935, preserved in the archives of the Regional Court in Łódź, the end of his sentence was noted on February 1939.

Nosek accused

The taking down of Bornstein’s criminal organisation was one of the biggest successes of Weyer. As he said himself, it also cost him a lot of health. Due to a worsening cardiac disease, he asked for a transfer to another unit. It was established that since June 1935 he served as the chief of the Administration of the Province State Police in Tarnopol, and then in April 1936 he ended his service in the State Police in the rank of a senior commissionaire and was honourably discharged.

Several months later, which was quite predictable, the “Blind Max” scandal ended up in court once again, this time due to the unfinished case of deputy inspector Nosek. His four-days long trial began on October 12th1936 before the Regional Court. The event aroused enormous interest among the citizens of Łódź, as it regarded a well-known, high-ranking officer of the State Police. There had never been a similar case in the pre-war history of the city, and the finding of the investigation were a shock to the public. Each day of the trial brought to light more and more details of informal and compromising relations between a respected to this point officer of the law and the Łódź underworld.

In the indictment, Nosek was accused of, among other things, tolerating and hiding crimes committed by Bornstein, protecting the gangster and encouraging him to write anonymous letters defaming senior commissionaire Weyer. The accused defended himself claiming that he had nothing to do with the messages: “I am – he stated – morally molested by the accusations of inspiring to write the anonymous letters”. His contacts with the gangster were supposedly only of professional character. He claimed to had met Bornstein in 1932, enlisting him after several months as a confidential informer. He then allegedly helped him i.e. catch a group of counterfeiters organising illegal crossing of the Polish-German border or expose a mocked burglary of a store in Łódź.

The verdict was announced on October 15th 1936 – Nosek, a former member of the Polish Military Organisation (POW) serving in the State Police since November 1918 – was found guilty of professional negligence and sentenced for a year and a half in prison, lowered to 8 months due to an amnesty. However, he only got to prison in the beginning of August 1938 following an appeal trial and a rejection of a dismissal by the Supreme Court in Warsaw. After the president decided not to use the prerogative of mercy the sentence of 8 months in prison came into force and Nosek ended up in jail in Nowy Sącz. At the time, he was no longer a police officer. On the initiative of the chief-of-police he was discharged from service, as a doctor declared him unable to work, and was given a retirement pension. After serving the sentence, he returned to his hometown Łańcut, where his wife Józefa and daughter lived. There, by the end of the war, he was murdered by the NKVD on February 2nd 1945.

Weyer’s fate was quite different. The outbreak of the war against Germany surprised him and his family in Łódź. After the authorities left the city, he engaged in the work of the newly created Citizens’ Committee, where he took command of the new Citizens’ Militia [not to confuse with the post-war, communist Citizens’ Militia; translators’ annotation]. When the German troops took over the city, Weyer was arrested on September 12th1939 by the officers of a special intelligence group. He later stated that the Germans beat him up and blackmailed him into serving in Kriminalpolizei. From the preserved German archives it is clear that he was hired as an assistant official of the German criminal police. In February 1940, he also received a German citizenship.

Bornstein managed to get through to the USSR where he worked in a tank factory in Ural. He returned to Łódź in the beginning of 1946, and when he only found out that Weyer was in the country, he decided to settle the score with the former senior commissionaire of the State Police.

When in January 1945 the Soviets entered the city, Weyer was immediately arrested by the NKVD. He ended up in a Soviet gulag from which he returned, after almost three years, on December 15th 1947. To his surprise, on the very next day he was arrested once again. This detention was caused by a tip given to the Regional Prosecution in Łódź. The author of the message was… Bornstein. It turned out that after the war broke out he managed to get through to the USSR where he worked in a tank factory in Ural. He returned to Łódź in the beginning of 1946, and when he only found out that Weyer was in the country, he decided to settle the score with the former senior commissionaire of the State Police.

Following a long investigation, no sooner than on January 27th 1949 Weyer was accused of helping the Germans in the criminal police, and later, as its officer of taking part in searches, questionings, beating and shooting the civilian population. As a result of a complicated trial lasting several months, the Regional Court in Łódź sentenced him to three years in prison, acquitting him from the most serious charge – shooting civilians. Weyer died five months later, on May 31st 1950, in a prison on Sterling street in Łódź. According to a doctor, the cause of his death was advanced tuberculosis.

The story of “Blind Max” continued for ten more years. Before his death, he managed to cause another huge scandal in the Health Department of the Presidium of the National Council in Łódź by blatantly demanding, despite the lack of vacancies, to send him to a sanatorium during the summer. Because of that, in the middle of 1954, an official complaint was filed against him to the Łódź Committee of the Polish United Workers’ Party. The irritated party activists complained that Bornstein not only constantly “shouted anti-Semitism” but was also claiming to have suspicious relations with the highest state official.

The most infamous thief and scoundrel of the city of Łódź died on May 18th 1960, at the age of 70. His grave is located at the Jewish Cemetery (on Bracka street) on the opposite side of the mausoleum of the richest citizen of Łódź in the city’s history – Izrael Poznański.