The document included a protocol stating that the moment Poland and the Soviet Union would resume their diplomatic relations:

“The Soviet government would pardon all Polish citizens currently imprisoned in the territory of the USSR, held as POWs or jailed under other conditions.”

This promise was fulfilled on August 12, 1941, when the Presidium of the USSR Supreme Council announced a decree on the “amnesty” of Polish citizens, repeating the aforementioned protocol word to word.

A signal from Sikorski

This act had no precedence in the history of the Soviet state. For Poles kept in gulags, prisons or places of forced deportation it meant a change of fate for the better, though; unfortunately, not for all of them (in reality, the Soviet authorities followed the “amnesty” decree very selectively).

It is worth reminding, that the “amnesty” for Polish citizens was born in pain. After all, it was not obvious for the Soviet authorities that they should free the citizens of the country with which they were about to resume diplomatic relations and make a military alliance.

The “amnesty” for Polish citizens was born in pain. After all, it was not obvious for the Soviet authorities that they should free the citizens of the country with which they were about to resume diplomatic relations and make a military alliance.

The first step towards bringing back the freedom of Polish citizens repressed by the Soviet authorities after September 17, 1939, was the radio speech by the Polish prime minister, general Władysław Sikorski. He gave the speech a day after Germany attacked the USSR (June 23, 1941). In the speech, the head of the Polish government demanded the release of “thousands of Polish men and women” from Soviet prisons, emphasising that a quarter of a million of POWs were “idly withering away” in Soviet camps.

Sikorski’s speech was undoubtedly an offer of cooperation made to the Soviet Union, and that is exactly how the Soviet authorities understood it. As a result, with Great Britain’s mediation, negotiations between Poland and the Soviet Union began. An alliance between the two countries was the “stake” of these talks.

Hesitation of the Soviets

The negotiations began on July 5, 1941, when Sikorski met with the Soviet ambassador in Great Britain - Ivan Mayski. When discussing various aspects of their bilateral relations, the head of the Polish government did not forget to demand the release of Polish POWs and political prisoners held in the USSR. Mayski promised to pass that demand to his government.

The British side took the brunt of the negotiations. After a few days, it managed to get the Soviet authorities to agree to the release of political prisoners, although it was to be included in the secret part of the pact.

The next meeting between Sikorski and Mayski took place on July 11, 1941. On that day, the Soviet ambassador agreed to the release of POWs, describing the matter as quite simple and not requiring any further discussions. He did, however, fail to mention the matter of releasing the Polish political prisoners, and there was no mention of it in the first draft of the Polish-Soviet pact, prepared by the latter. The Polish prime minister spotted this fact and demanded for the draft to be amended by this additional point on the release of all Polish citizens. Mayski’s response was ambiguous. He said the Soviet government’s stance on this matter is unknown and promised to learn more. Nevertheless, he did assume that the release of all prisoners could be an issue for his government.

In the end, the matter was resolved negatively in the amended draft of the Polish-Soviet act, presented by Mayski on July 17, 1941. There was no additional point on the release of political prisoners. In response, on July 21, 1941, Sikorski once again added this point to the pact. It was of fundamental importance for him and was the conditio sine qua non for making an alliance with the Soviet side.

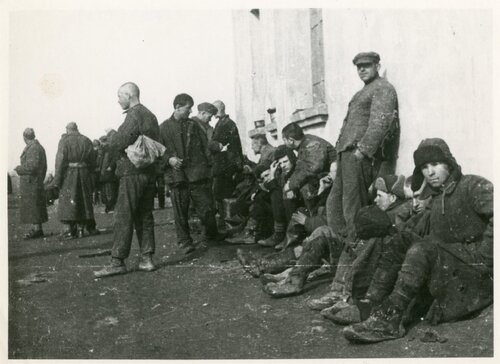

An inscription on the back of the photo says: Stalin’s paradise… After the “amnesty”. Polish soldiers freed from Soviet gulags after joining Gen. Anders’ Army, December, 1941. Photo from the archives of the Institute of National Remembrance (acquired from the Józef Piłsudski Institute in the United States)

An inscription on the back of the photo says: Stalin’s paradise… We are getting together after the amnesty.Polish soldiers freed from Soviet gulags after joining Gen. Anders’ Army, December, 1941. Photo from the archives of the Institute of National Remembrance (acquired from the Józef Piłsudski Institute in the United States)

British diplomatic “help”

At this stage, the British side took the brunt of the negotiations. After a few days, it managed to get the Soviet authorities to agree to the release of political prisoners, although it was to be included in the secret part of the pact (the Polish authorities assumed it was for propaganda reasons). Further negotiations led by the British embassy in Moscow with Stalin’s and Molotov’s participation led to their agreement to include a general clause on the release of POWs, as well as deported and political prisoners, in the unsealed content of the pact.

For Stalin, as it seems, the fact he was forced to release Polish political prisoners was a tough pill to swallow for a long time. In a conversation with the Polish ambassador to the USSR, professor Stanisław Kot, on November 14, 1941, he said with clear reproach that as a result of announcing the “amnesty”, the Soviet authorities released all Poles, including those who came to the Soviet Union as “Sikorski’s agents” to blow up bridges and murder “the Soviet people”. Of course, his statement that “all” Poles were released from prison could not be further from the truth. One of the most important aspects of the Polish embassy’s work in the USSR was the fight for a complete fulfilment of the “amnesty”.