While contemplating the causes of the outbreak of the January insurgency, it is important to note the policies of the two major Polish parties of that time (although there were more of them than the typically mentioned “reds” and “whites”), but also to include the wider European perspective i.e. revolutionary movements in Russia or the victories of Giuseppe Garibaldi in the uniting Italy. It is also important to take into account the rapid course of events in 1862 and 1863, including the forced call-up to the Tsars’ army and the immediate reaction of the families touched by it. The hasty, pre-mature outbreak of the January Uprising, the so-called “cutting of the cyst” — as described by margrave Aleksander Wielkopolski — was also the result of the constantly harsher repression policies led by the occupier against the Poles, who dreamed of freedom.

Four years after Tsar Alexander’s visit to the capital of the Kingdom of Poland, a series of events took place which grew and pulsated like the internal lava of Adam Mickiewicz.

It is impossible to criticise the uprising’s outbreak without recalling the events which turned Poland into a brewing pot — after its people were beaten with a whip, murdered, imprisoned in the Warsaw Citadel and sent to Siberia. The blood of hundreds of innocent people killed in the capital did not wash away from memory as quickly as it did from the Warsaw pavements.

The period of patriotic-religious demonstrations in Warsaw in 1861, ending with the introduction of martial law and the closing of churches, was the prelude to the uprising. If one were to search for the moment when the insurgency began to form, they would have to go back to the year 1860.

The year 1860

When in May 1856, the new Tsar, Alexander II came to Warsaw for the very first time, everyone expected that he would be kind to Poland, that a new era would begin, that the echoes of “post-Sevastopol thaw” would result in the widening of liberties and the granting of long-promised freedoms. The enthusiasm died very quickly. The blue-eyed monarch did not beat around the bush and immediately showed them how he imagined his rule in Poland: “Point de rêveries, messieurs, point de rêveries” (“No dreams, gentlemen, no dreams.”) — he said. And then added: “What my father did, he did well, and I intend to keep that.”

The Tsarist vision of “staying on course” was met with the response of the young, Polish generation. It was them, the students of the Warsaw Academy of Arts, the Medical-Surgical Academy (the university was closed at the time) or the Real School Junior High who more and more openly manifested the Polish spirit of freedom.

Four years after Tsar Alexander’s visit to the capital of the Kingdom of Poland, a series of events took place which grew and pulsated like the internal lava of Adam Mickiewicz [prominent romantic poet, translator’s annotation].

First, in June 1860, there was a funeral of the general’s wife, Katarzyna Sowińska, the widow after a legendary commander of the November Uprising. The youth carried her casket on their shoulders all the way to the Powązki Cemetery. During the funeral procession, they began singing patriotic songs. There wasn’t a single leaf left on the bushes surrounding the grave, as everyone wanted to have a souvenir from the event.

Actions of “minor sabotage” were a strong symbol of resistance against the occupier, especially during the October “summit of three caesars”, when monarchs of Poland’s partitioners came to Warsaw. The city was seething. Someone spilled a stinking liquid at a play in the Grand Theatre; on the posters announcing the play Two Warsaw thieves some boys painted over the word “two” and changed it to “three”.

But it were the celebrations of the 30th anniversary of the outbreak of the November Uprising which turned out to be the most spectacular. Massive crowds gathered at the Leszno district of Warsaw, in front of the Carmelite church which used to be a tsarist prison during the 1830 insurgency. People brought candles which they laid in front of the statue of the Holy Mary (on a side note, it survived all wars and conflicts, the destruction of Warsaw and even the relocation of the church in the postwar years; the date 1859 is engraved on the back of its base). The people held portraits of Tadeusz Kościuszko and Jan Kiliński. An organised academic youth group led by Karol Nowakowski, a student of the Academy of Arts, appeared among the crowds of Warsaw residents. His friends handed out lyrics to patriotic songs to the gathered people, and he himself began singing God Save Poland [Boże, coś Polskę] by Alojzy Feliński, but with the changed words - “homeland” instead of the “Tsar”. Hence, for the first time ever, Poles sang “Homeland, freedom, let us have again, Lord.” Then, Poland Is Not Yet Lost [Mazurek Dąbrowskiego, Polish national anthem since 1926] and With the smoke of the fires [Z dymem pożarów].

Still singing, the crowd marched towards the Old Town. The Russians observed the procession, but did not intervene. One could even say, that it was in that moment that the flame of freedom began burning. It turned out that a peaceful, religious demonstration, a prayer and a song, were a problem for the Muscovites. They had no idea how to deal with something which wasn’t an aggressive protest or armed resistance. However, they quickly realised that it was an equally dangerous form of defiance. They decided to suppress the next demonstrations. With the use of force.

Laying of wreaths by the veterans of the January Uprising in the Belvedere Chapel, January 1936. The veterans in the picture are, among others, Mamert Wandali, Maria Fabianowska, Władysław Dunin-Wąsowicz, Wiktor Malewski and Antoni Tarnawski. Photo from the collections of the National Digital Archives

Remembering Olszynka - February 25, 1861

The January Uprising is often referenced in the materials published by the underground Solidarity movement. There are indeed lots of similarities between the two movements — the one from before January 22, 1863, and the one from 1980, which was brutally dispersed during the martial law. But earlier incidents as well: Poznań, 1956; December, 1970; and Radom, 1976 — all these events, remembered by many Poles from their own experiences, can help us understand the atmosphere of the time before the outbreak of the January insurgency.

New Year’s Eve, and then January 1861, were the time of a “mourning carnival”. The New Year’s issue of the Illustrated Weekly with patriotic drawings on the cover was largely confiscated before it ever reached its readers. A citizens’ ban on parties was in place in Warsaw; if anyone dared break it, they had to be ready to have their windows broken.

The funeral of the five fallen, which took place in the capital on March 2, 1861, turned into an enormous demonstration, counting more than a hundred thousand people. Representatives of all social statuses marched behind the caskets, joined by representatives of all religions, including the Warsaw rabbis.

Another important anniversary for Poles was drawing near. On the 25th of February, Poles were celebrating 30 years since the battle of Olszynka Grochowska. Huge celebrations were planned in the grochowskie fields. At that time, there was no permanent crossing over the Vistula river. A new bridge was under construction near Nowy Zjazd and the Royal Castle, which was later called the Kierbedź bridge to honour its designer and engineer. For the time being, the residents of Warsaw were using the floating bridge. The Tsar’s governor, prince Mikhail Gorchakov, who replaced Wincenty Krasiński in 1856, remembered the battle of Olszynka very well, as he took part in it himself. He observed the preparations to the celebrations with anxiousness. He was then eager to listen to his advisors and to deny the patriotic demonstration at the fields of Grochów, he ordered… to take the bridge apart. Cutting off Poles from the place of the battle did not bring the desired outcome, on the contrary, it only made the situation worse. Varsovians decided to honour the previous generation anyway and they gathered in the Old Town. Leaflets with a patriotic proclamation were spread around town. As recalled by the historian of the January Uprising, Russian Nikolai Berg: “they were not only handed out to pedestrians, but also glued on the walls of the buildings so openly, that the police caught a student of the Academy of Arts red-handed, with the brush, glueing paste and the proclamations.”

People flocked to, among others, the Gołębia and Freta streets, in front of the Dominicans’ and Paulines’ churches. A horse-wagon delivered the standards of Poland, Lithuania and Ruthenia. The crowds marched towards to the Old Town Square, Polish patriotic songs filled the air and pictures of the saints were handed out from the windows. The crowd wanted to reach the Radziwiłłowie Palace, where the discussions of the Farmers’ Association were taking place. They wanted to “force the Association to make an active political speech” (as quoted by Walery Przyborowski). Street vendors made some room at the Old Town Square, moving their stalls up against the walls of the tenement houses. There, the demonstration was stopped by the cavalry gendarmes, led by chief of police Fyodor Trepov, who started to tussle with the youth. When he wanted to pull away a standard from the hands of a student, Krajewski, the young man punched him in the jaw. That was the moment a popular, sarcastic song was born in Warsaw: “At the Old Town, by the fountain’s grace, Fyodor Trepov got punched in the face.” Nevertheless, the end of the day was not as amusing — the gendarmes charged the crowds on horseback and smacked the people with the blunt sides of their sabres. The crowds ran in panic. Many people got arrested and sent to the Warsaw Citadel.

The Five Fallen

Despite all that, two days later, on February 27th, there were even more demonstrations. The Poles demanded the freeing of those arrested in previous protests, including Karol Nowakowski (the student singing in front of the church in Leszno). Cossacks dispersed the crowds gathered at the Castle Square and the Krakowskie Przedmieście street using whips. The Varsovians responded by throwing rocks and pieces of ice at them. Suddenly, the Russian infantry, on the order of gen. Wasyl Zabołocki, opened fire at the unarmed crowds. Unit after unit fired at the people. Five people were killed on site: Filip Adamkiewicz, a tailor’s apprentice; Karol Brendel, a construction worker; two landowners, Marcel Karczewski and Zdzisław Rutkowski; and a fifteen-year-old, junior-high student, Michał Acichewicz. The boy’s body was raised above the crowds and carried to his parents’ house. The remaining four victims were laid on the tables at the billiard hall of the European Hotel.

It was the middle of the 19th century. No one in the world could ever imagine the military opening fire on unarmed civilians in the streets. This was a violation of all the rules of civilisation.

The funeral of the five fallen, which took place in the capital on March 2, 1861, turned into an enormous demonstration, counting more than a hundred thousand people. Representatives of all social statuses marched behind the caskets, joined by representatives of all religions, including the Warsaw rabbis. The Russians decided that the Poles should keep the order at the funeral procession. Young, Polish “constables” fulfilled that task expertly. That was the beginning of the so-called Polish time, meaning a somewhat limited local government rules for the Poles.

The massacre of April 8, 1861

In the beginning of April, the Russians disbanded the Agronomic Association of count Andrzej Zamoyski, which outraged the Poles and was widely commented across the country. The capital was uneasy. The Muscovites expected unrest. On the night from April 7th to April 8th, margrave Wielopolski presented prince Gorchakov with his project of “an act on crowding.” The act allowed the military to use weapons if crowds did not disperse after a three-time warning and a signal of the drums. A few posters announcing the new law were hanged in the city, but most of its residents had no chance to read them. The crowds began gathering at the Krakowskie Przedmieście and Castle Square, as usual.

The military marched from the barracks and stood in front of the Royal Castle. Governor Gorchakov watched from his window, and the entire operation was led by gen. Stepan Khrulev. The cossacks charged once again. The soldiers hit the crowds with whips, spears and backs of their sabres. Blood spilled, but the people did not retreat. Women kneeled on the ground. People prayed and sang. A procession approached from the Miodowa Street led by Karol Nowakowski, freed from the Citadel, holding a wooden cross. The student was singing a supplication with his beautiful, powerful voice. Meanwhile, a Russian officer called on the crowds to disperse three times. Gorchakov ordered Khrulev to “get the young one alive.” The soldiers, making room through the crowd with the backs of their rifles, reached Nowakowski. They began fighting. They used their rifles, while he fought with the cross, which he swung back and fourth like a medieval sword. In the end, they grabbed him and carried towards the Citadel. A young Jew, Michał Landy, picked up the cross from the ground. He picked it up… and fell to the ground, hit with a bullet.

The period of patriotic demonstrations from the beginning of 1861 and the bloody Russian repressions turned the capital into a barrel of gunpowder. The blood of hundreds of murdered people, fathers, mothers, brothers and sons could not be forgotten. The following months only added fuel to fire.

The army opened fire. More and more units of the infantry, standing in the square and in back alleys, fired salvo after salvo. Panic broke out. People were running away, trampling each other. And the onslaught continued. Corpse after corpse fell to the ground.

A man, wounded, walked along the walls of the tenement houses, leaving behind him a bloody trail, stretching for many metres. The blood was flowing in the gutters in streams. It’s not known precisely how many Poles died that day. The Russians were throwing bodies into unmarked graves and to the Vistula river. The Austrian ambassador wrote about 110 killed people; Russian historian Berg mentioned 200, while freedom activist Agaton Giller believed there might had been as much as 500. By name, we know of 98 people. This event alone would be enough for an armed resistance. It was truly a massacre; there were multiple salvos into the crowds and grape-shots from the cannons of the Citadel.

Martial law and the closing of churches

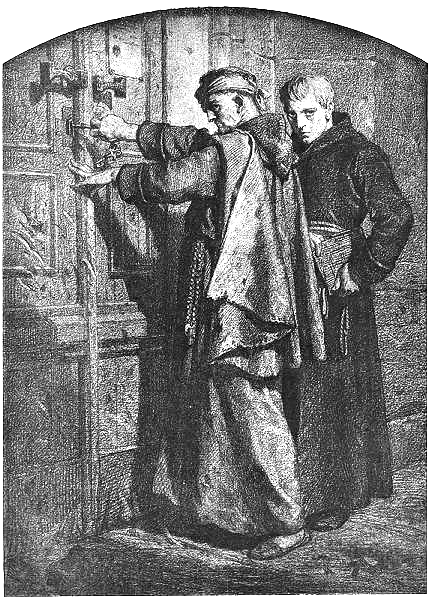

The situation was growing more tense by the day. Gorchakov died at the end of May. He was replaced by Nikolai Sukhozanet, followed by the next governor, count Karol Lambert. Archbishop Antoni Fijałkowski died in October, 1861, and his funeral became the next huge demonstration. Dozens of patriotic-religious ceremonies took place in these several months. An enormous ceremony took place in Horodło on the anniversary of the Polish-Lithuanian union. Preparations were underway for the commemorations of the anniversary of the death of Tadeusz Kościuszko, when the governor broke and introduced the martial law. The people praying in churches for the soul of Kościuszko on October 15th were attacked by the Russians. The army surrounded the temples. In the night, the Muscovites began their raids — they burst into the churches, beat the faithful, dragged them out by force and led to the Warsaw Citadel. Several thousand Varsovians were imprisoned. The priests made the dramatic decision to close down the temples. This moment was caught on the famous graphic by Artur Grottger, where a father is turning the key in the doors of a church. Rabbis and pastors joined the Catholic clergy in their protest.

Thus, the period of patriotic demonstrations from the beginning of 1861 and the bloody Russian repressions turned the capital into a barrel of gunpowder. The blood of hundreds of murdered people, fathers, mothers, brothers and sons could not be forgotten.

The following months only added fuel to fire. And when the Russians prepared lists of people who were to be forcefully conscripted to their army for dozens of years, with sons of Polish patriotic families included by names, the situation spiralled out of control. Young people began fleeing to the forests, where they intended to hide and defend themselves. The uprising would break out anyway, so the National Central Committee had to decide whether to take responsibility for its course. The manifest of the January Uprising, written by poet Maria Ilnicka, mentioned the “wild barbarism of Asia”, and everyone vividly remembered what it ensued in these years.

The article comes from issue 11/2017 of the Bulletin of the Institute of National Remembrance