I recall the day the Riga peace treaty was signed. I was in Cracow on that day. The city was extremely joyful - there were marches, rallies, speeches.

And suddenly a young girl, a student from the Jagiellonian University, stormed the platform.

-Fools! What are you happy about? About the fact that you sold half of my homeland, Belarus, to the Russians?

The crowd swayed anxiously.

-What is she talking about? She’s a lunatic!

Grażyna Lipińska, If I ever forget them…, Warsaw 1990, p. 159

Grażyna Lipińska, Jeśli zapomnę o nich…, Warszawa 1990, s. 159

Two concepts regarding the eastern border clashed in Poland at that time. The federation idea, proclaimed by Józef Piłsudski, assumed the creation of a separate Ukrainian state to the east of the Republic of Poland, connected with Poland by a close alliance, and a federation with Lithuanians and Belarusians in the territory of the former Grand Duchy of Lithuania. The idea of incorporation, represented by Roman Dmowski and the National People's Union, provided for the incorporation into Poland of those lands in the East, where Poles constituted the majority of the population, and the assimilation of local residents of non-Polish origin. As a consequence, a nationally uniform state was to be created. According to Dmowski's plan, Poland would include: Eastern Galicia, Lithuania and the Belarusian lands up to the Berezina River.

Allies

Among the potential members of an alliance or federation with Poland, Ukrainians were the most involved in the project. In 1919, the leader of the Ukrainian People's Republic, Symon Petliura stated:

“The fight against the Bolsheviks is not over yet. It should be noted that the greatest obstacle in this matter so far has been our isolation from our neighbors, and primarily from Poland. This isolation has hurt us all the more because we have common goals in this fight.”

On April 21, 1920, the Republic of Poland and the Ukrainian People's Republic signed a political agreement defining the common border of both countries and the principles of future cooperation. Three days later, a military convention was concluded.

It recognised Polish and Ukrainian troops as allied and fighting "under the supreme leadership of the Polish Army Command".

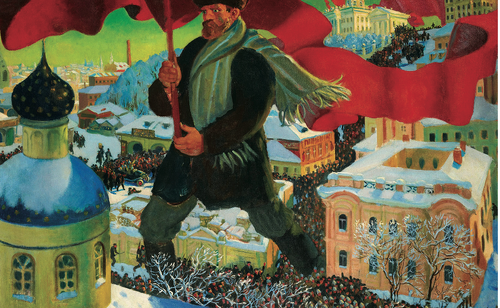

The Polish-Bolshevik war was a clash of two different civilisations - the Western world, built on Christian foundations, with bloody totalitarianism, which was characteristic for its imposed atheism.

The treaty also guaranteed that in the areas of right-bank Ukraine liberated from the Bolshevik rule, an administration would be created under the government of the Ukrainian People’s Republic. The retreat from Kiev shattered these plans.

Lithuanians rejected any joint federation plans as they wanted to create their own nation-state with the capital in Vilnius. The talks with Belarusians ended with declarations of creating Belarusian autonomy within the reborn Polish state. It should be remembered, however, that an important role in the Polish army was played by the Lithuanian-Belarusian Division, formed on November 26, 1918 from volunteers who wanted to defend the borders of the Republic of Poland against the Bolshevik invasion, as well as the Russian People's Volunteer Army, commanded by General Stanisław Bułak-Bałachowicz, as well as officers and Russian or Caucasus soldiers.

For life or death against the Bolsheviks

The Polish-Bolshevik war was a clash of two different civilisations - the Western world, built on Christian foundations, with bloody totalitarianism, which was characteristic for its imposed atheism. Both sides of the conflict were very young.

On October 12th, a ceasefire was signed in the Latvian capital, Riga, between the Republic of Poland and the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic and the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic. In addition to Minsk, Polish soldiers then occupied Kojdanów and Słuck - in the north, and Szepetówka, Płoskirów and Kamieniec Podolski - in the south.

The reborn Republic not only fought militarily for all its borders, but also had to face enormous economic problems and make a great attempt to unite the various systems inherited from the three partitioners. Bolshevik Russia fought for survival, bloodily suppressing all attempts of their political opponents, the democrats and monarchists, to resist. Poles wanted a free, independent homeland. The Bolsheviks aimed at bringing about the global communist revolution "over the corpse of independent Poland" - as they called it.

The Polish Army captured Kiev in May 1920, while the Red Army approached Warsaw in August. Then there was a breakthrough in the war: Poles led by Marshall Piłsudski achieved a spectacular victory, strengthened by the battle of the Nemunas in September. The defeat of the Bolsheviks came as a shock to their leaders. On October 15th, 1920, the Polish Army entered Minsk. Three days earlier, on October 12th, a ceasefire was signed in the Latvian capital, Riga, between the Republic of Poland and the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic and the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic. In addition to Minsk, Polish soldiers then occupied Kojdanów and Słuck - in the north, and Szepetówka, Płoskirów and Kamieniec Podolski - in the south. There was great satisfaction with the military successes achieved, but at the same time tiredness of the fights taking place in the native lands continuously since 1914.

Shortly before the ceasefire came into force, the Polish Parliament demanded from the Supreme Command of the Polish Armed Forces to apply the provisions of the ceasefire to non-Polish troops that took part in the war with Soviet Russia on the side of the Republic of Poland. The forces of Ataman Petliura and General Bułak-Bałachowicz had to leave the territory of Poland by November 2nd, and if they returned under arms, they were to be disarmed and interned in the camps. The Ukrainians considered this decision to have been treason.

After the truce came into force, the units of the Ukrainian People’s Republic and General Bułak-Bałachowicz undertook military operations against the Bolsheviks. The Ukrainian army, however, had to leave its country, under the pressure of overwhelming enemy forces, and on November 21st it crossed the border at Zbrucz, while Bałachowicz's forces retreated beyond the armistice line in Polesie on November 28th. In May 1921, Piłsudski arrived at the internment camp of Ukrainians in Szczypiorno and apologized to them, explaining that this was necessary for political reasons. Petliura in the newspaper "Son of Ukraine" commented on his and his nation's situation:

“In the worst hours of national and state misfortunes, Ukraine was honestly and faithfully with Poland. She carried her weight, gave her to fight her best sons, Ukrainian Cossacks - knights. She washed and defended Polish borders with her blood. Why at the moment, at the peace conference, did none of the Polish representatives mention the fact that Ukraine is an ally of Poland? Why is it so? Is it not understandable that this is an insult to all those Ukrainians who with the Polish nation fought back the Bolshevik onslaught, shedding their blood and sacrificing their lives?”

Negotiations

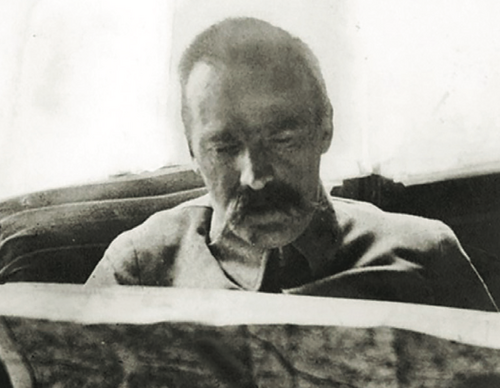

The Polish armistice delegation was headed by the then deputy minister of foreign affairs, and also a politician of the people's movement, Jan Dąbski; the Soviet side was initially led by Karol Daniszewski, who in September 1920th was replaced by the seasoned diplomat Adolf Joffe. It was ironic that Dąbski, the leader of the "bourgeois" delegation of Poland, was born to a peasant family in Galicia, while Joffe, representing the "workers and peasants" government of the Bolsheviks, was the son of the richest representative of the bourgeoisie in Crimea.

The first success of the Bolsheviks was to obtain consent from the Polish delegation that two entities formally representing Soviet Russia and the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic should sit on their side. Thus, the Polish side broke the Piłsudski-Petliura agreement. Moreover, the Russians also spoke on behalf of the Belarusian Soviet Republic.

The Polish delegation consisted of ten people, most of them representatives of the strongest parliamentary groups. The borderland circles accused Dąbski of his lack of knowledge of Russia and Bolshevism. The dominant role among parliamentarians was played by: Stanisław Grabski, representing the People's National Union, a supporter of the incorporation concept, and Leon Wasilewski, an expert on eastern issues, who opted for the federation concept.

The dispute between the Poles concerned mainly Minsk and the Minsk land: should they be incorporated into the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth or not? Grabski believed that the city would be - as the main center of Orthodoxy in Belarus - a strong seedbed of Russian nationalism in Poland. Wasilewski, in turn, wanted to establish centres of the Belarusian and Ukrainian national movement on Polish territory, as he was afraid that they would otherwise arise on the Soviet side. He predicted that the Soviets - having Minsk and Kiev in their hands - would try to instigate a freedom movement within the borders of the Polish state in the future. At a meeting of landowners from Belarus in Warsaw on October 24th, 1920, Roman Skirmunt stated:

“In the future, Mr. Grabski will be called the father of the Belarusian insurgency in Poland, because both parts of Belarus will always strive to unite, while Poland has a smaller part. The Belarusian movement, which Mr. St [anisław] Grabski is so afraid of, was not terrible, he turned to Poland, he sought support in it, he wanted to take Western culture from it, he wanted to join it. Now this movement will become a tool in the hands of the future Russia and will turn against Poland.”

The first success of the Bolsheviks was to obtain consent from the Polish delegation that two entities formally representing Soviet Russia and the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic should sit on their side. Thus, the Polish side broke the Piłsudski-Petliura agreement. Moreover, the Russians also spoke on behalf of the Belarusian Soviet Republic.

Wincenty Witos, the then Prime Minister of the Republic of Poland, described the reaction of the Polish population to the first news about the direction of the negotiations in Riga:

“The hardest and the worst was with the delegations of the Polish people who were to remain on the Russian side. These delegations came from Kamieniec Podolski, Minsk, Berdyczów, crossing the borders in secret, risking their lives and begging with tears that Poland would not give them to the Bolshevik torturers who would shame their wives and daughters, destroy their enormous achievements and Polish culture [...]. It was sorry to see those people, mature men, crying and drifting from exhaustion, and unpleasant to hear complaints about the delegation.”

“Poland is not coming for us…”

The second article about the recognition by both sides of the independence of Ukraine and Belarus was very important in the treaty. On the basis of the seventh article, Russia and Ukraine ensured the free development of culture and language, and freedom of religious practice to people of Polish nationality in Russia, Ukraine and Belarus. The same rights were granted to representatives of the Russian, Ukrainian and Belarusian nationalities in Poland.

Bolshevik Russia ratified the Treaty of Riga on April 14th, 1921. Mikhail Kalinin signed it as the formal head of state. The Sejm of the Republic of Poland accepted the agreement a day later, and on April 16th it was signed by the Head of State, Józef Piłsudski. On April 17th, the treaty was approved by Soviet Ukraine. The exchange of ratification documents between the representatives of the Polish government and the Russian and Ukraine Socialist Republics took place in Minsk on April 30th, 1921. The final version of the agreement was definitely less favorable for Poland than the peace preliminaries of October 12th, 1920. In the ending of her debut book, Pożoga, Zofia Kossak wrote:

“Poland is not coming for us ... It is not coming. I don't want to. I don't need… […] So everything was for nothing. Our perseverance, efforts, so much hope, faith, so much love, waiting - useless and undesirable…”

National treasures

Polish claims included the return of war trophies, libraries, archaeological and archival collections, works of art, relics and all collections of historical and cultural value, taken to Russia after January 1st, 1772. The Soviets inhibited the transfer of property and demanded detailed documentation of title deeds.

By May 1922, the equipment of the Royal Castle had returned to Poland, including the painting by Jan Matejko Battle of Grunwald and the monument to Prince Józef Poniatowski, taken after the November Uprising. The Russians gave the Crown Archives, 7193 manuscripts, including The Załuski libraries, original parliamentary diaries, letters and notes from the Radziwiłł, Chodkiewiczs, Wincenty Kadłubek, Jan Długosz, Adam Naruszewicz, Tadeusz Kościuszko and Joachim Lelewel, and partly the archives of the governor offices of the Congress Kingdom. By 1924, the restoration of the tapestries had been completed - 136 fabrics commissioned by Sigismund II Augustus in Brussels were delivered in batches. 70 thousand numismatic items, a certain number of tapestries, the banners of the Legions of Dąbrowski, and 10 thousand prints remained in Russia. Out of 20 thousand church bells seized by Russia during the First World War, including those from the 12th century, 7,000 returned to Poland.

Prisoners and civilian population

A serious problem on both sides was the exchange of prisoners of war. The exact number of Polish POWs is not known - historians assume that there could have been between 44 to 60 thousand of them. The conditions in the Soviet camps were comparable to those in which Red Army soldiers were held on the territory of the Second Polish Republic. It is difficult to determine the number of deaths from diseases. By October 1921, nearly 26.5 thousand people returned to the country. Over 20,000 never crossed the border and with a high degree of probability it can be concluded that most of them did not survive captivity, were shot or died of exhaustion and starvation.

It is estimated that 80-85 thousand prisoners of war were held in Polish captivity. About 65 thousand people left for Soviet Russia as part of the exchange. In Poland, as a result of the epidemic, 16-18 thousand people died in captivity. According to Nikita Petrov from the Russian Memorial Association, many Soviet prisoners of war from 1920 who returned from Poland to their country were shot in the late 1930s on the orders of Stalin, who had them murdered as part of the anti-Polish operation of the NKVD.

By April 1924, 1.1 million people had been resettled from the USSR to Poland, of whom Poles constituted approximately 20 percent. The others were mainly Belarusians, Ukrainians and Jews. Several thousand people left in the other direction, to the Soviet Union.

Fate of those who stayed with the Soviets

The Polish population which remained within the borders of the USSR - estimated at 1-1.5 million people - was subjected to repressions from the beginning of the Bolshevik rule. As a bridgehead of the future communist power in Poland, the Julian Marchlewski Polish National Region was established in 1925 in Ukraine and the Feliks Dzerzhinsky Polish National Region was established in Belarus in 1932.

During the debate in the Polish parliament on the ratification of the treaty, Henryk Grabowski, the great-grandson of Tadeusz Rejtan, shouted from the gallery to the audience: "Disgrace!" and spread leaflets protesting against the renunciation of the eastern territories (he was murdered by the Soviets in 1939).

Both autonomies were abolished in 1935 and 1937, respectively, and a significant part of their inhabitants were deported to Kazakhstan. On the basis of order No. 00485 of August 11, 1937, the anti-Polish operation of the NKVD began, during which - according to the data of the Memorial Association - over 143 thousand people were arrested, while almost 140 thousand were tried, including over 111,000 sentenced to death. Please note that these are minimal numbers. The victims of forced collectivisation of villages and the Great Famine in Ukraine in the years 1932-1933 should be added to the overall balance of losses.

One of the people deprived of their homeland and patrimony, Florian Czarnyszewicz from near the Berezina river, wrote:

“The news was terrible. [Kościk Wasilewski] informed me about the planned suppression of the Polish spirit and the nationally conscious Belarusians in the Soviet reality. [...] There are no longer, my brother, neither our rallies nor evenings, nor festivities, nor the whole former life. They cut pear trees in the field, plowed bushes, burned roadside crosses and shrines, and canceled annual holidays. […] Hundreds of thousands of our brothers were scattered over foreign and wild lands, condemning them to destruction. Brother, who will weigh their harm?! Who will measure their pain?! ”.

The situation of the Catholic Church in the USSR, definitely dominated by Poles, may be a reflection of their fate. In 1923, in the Soviet Union there were 1.65 million Catholics, 397 priests, and nearly 580 churches and chapels.

At the end of the NKVD "Polish operation" in 1938, there were two Catholic parishes; the vast majority of the clergy were murdered. A local Polish woman, Jadwiga Ejsmont, who met Grażyna Lipińska in 1940 in the Minsk prison, expressed the following complaint:

“We cursed the whole world for not only allowing the devils to oppress us for so long, but that during the purge it looked idly when they, like wild animals, tormented us, us who were already doomed. We cursed Poland and you for forgetting about us so easily”.

Vanishing rubles

The Treaty of Riga also provided for a payment for the Republic of Poland - as compensation for the contribution of the Polish lands to the building of the Russian economy during the partitions - 30 million rubles in gold at prices from 1913. The Polish side initially demanded 296 million rubles in gold and demanded the return of Polish gold reserves exported from Warsaw by the Russians in the 1840s, which was included in the peace preliminaries. The Soviet Union never transferred a single ruble to the Polish side.

In November 1927, Warsaw signed an agreement with the USSR on the return of some Polish cultural goods for the price of a complete waiver of the payment of gold rubles under the Treaty of Riga. The Commonwealth then regained the coronation sword called Szczerbiec, the Great Crown Banner and many paintings by European painters, including Rembrandt, Antoine Watteau and Bartholomeus van der Helst.

Reactions on both sides of the border

The reactions of the societies on both sides of the border were similar. The Polish delegation from Riga on its way back to Warsaw was enthusiastically welcomed at railway stations with military orchestras playing for it in many places. The Polish press commented enthusiastically on the results of the negotiations. A spontaneous demonstration took place in Moscow after the news of the signing of the treaty. Crowds of people carried banners with the words: "We demand immediate demobilisation!", "We demand amnesty for deserters!” and "Long live peace!”. Red Army soldiers broke up the demonstration. The Soviet press published nothing more than short announcements about the signing of the treaty and did not comment on this event.

However, not everyone shared the enthusiasm of the rest of the society. Marian Zdziechowski, an outstanding philosopher born near Minsk, professor at the University of Vilnius, wrote:

“As a proof of noble selflessness, as a tribute due to Soviet Russia, they gave her vast areas of land, whose sons had fought for the Polish cause until the last moment - they gave Minsk, knowing what terrible terror it would entail upon it. And all this with a light heart, without regret, without remorse, almost with triumph”.

During the debate in the Polish parliament on the ratification of the treaty, Henryk Grabowski, the great-grandson of Tadeusz Rejtan, shouted from the gallery to the audience: "Disgrace!" and spread leaflets protesting against the renunciation of the eastern territories (he was murdered by the Soviets in 1939). Writer Sergiusz Piasecki did not hide his disappointment as he recalled these events years later:

“Actually, I had nowhere to go, because my family stayed abroad, on the Soviet side. The peace made with the Bolsheviks was the beginning of my defeat. Throughout my service in the army, I was hoping that we would re-occupy Minsk; because hundreds of thousands of Poles were waiting for us there. There was even a good opportunity for it, but it was not taken. I felt that I was cheated. I had a grudge against those whom I helped to win the independence of their homeland, but who did not help us - volunteer soldiers - in doing the same ”.

Removal of allies

The final chord of the Riga arrangements were the restrictions which faced our existing allies. On the initiative of Deputy Minister Dąbski, on October 7th, 1921, a protocol providing for the deprivation of asylum rights in Poland of fourteen counter-revolutionary leaders was signed. Under this act, among others, former member of the Russian Political Committee in Poland, Borys Savinkov, as well as former chairman of the Directorate of the Ukrainian People's Republic, Symon Petliura (he had been in hiding in Poland until December 1923) and his closest associates had to leave Poland,. Years later, Ukrainian columnist Ivan Kedryn-Rudnytsky summed it up by writing:

“There have been many cases in the history of the world that an ally abandoned an ally, made separatist peace treaties with the enemy, tried to save the maximum for himself in a newly created situation. But it was always like that when you lost. The partition of Ukraine in Riga between Poland and Russia took place after the victory of the Polish-Ukrainian war against Soviet Russia. So it was a betrayal in the classic sense.”

On October 29th, 1921, after the expulsion of the Russian and Ukrainian counter-revolutionaries, a debate was held in the parliamentary committee during which the activity of Deputy Minister Dąbski was criticised. He was accused of neglecting state interests. As a result of the accusations, he resigned from his position.