Every time he came to his Fatherland, he showed his great love for it. He also addressed a patriotic message to Poles – which still hold its value today. Until the very end he thought and wrote in Polish. His last words: “Let me go to the Father’s home!” he also said in his native language.

One should not create the illusion of freedom

John Paul II talked about Poland almost everywhere, on the occasion of various speeches, meetings, addresses.

His last words: “Let me go to the Father’s home!” he also said in his native language.

He did so even during the Sunday contemplations after the Angelus prayer, which the world saw i.e. on December 13th 1981, when the dictatorship of Wojciech Jaruzelski introduced martial law in Poland and the pope appealed:

“Polish blood must not be spilled, because too much of it has been spilled already, especially during the last war. We need to do everything we can to build the future of our Fatherland in peace”.

Five days later, on December 18th, he wrote a letter to gen. Wojciech Jaruzelski demanding the bloodshed to stop:

“The events of the recent days, the news of killed and wounded Poles in relation to the martial law introduced on December 13th, force me to address you, Mr General with a strong request and sincere appeal to stop the actions which bring the shedding of Polish blood.”1

The pope also reminded that in the past two hundred years Poles were met with countless wrongs and a lot of Polish blood was spilled, hence he wrote:

“in this perspective of history, the Polish blood must be spilled no more; this blood can no longer burden the consciences and stain the hands of our Countrymen. I address you, General, with a strong request and demand to bring back the matters of improving the society, which had been led with peaceful dialogue since August 1980, to the same road. […] The basic, human desire for peace is what speaks for discontinuing the martial law in Poland. The church is the advocate of this desire. […] I appeal to your conscience, General, to the consciences of all the people who are now making decisions.”2

The pope spoke about Poles and for Poles. And when in 1983 he came to Poland which was still under the martial law, he came as a comforter, someone, who wanted to bring back hope and show unity with those who were suffering in any way.

Not easy is this Polish land, our Fatherland. You could say that during more than a thousand years of its existence it has never seized to be the land of various challenges. These challenges sometimes brought her greatness and glory. Other times – they brought suffering, and what’s more: danger, often mortal danger - said John Paul II during his pilgrimage to the homeland (1983)

I cannot visit all the sick, imprisoned and suffering. However, I ask them to be with me spiritually – he said at the Warsaw cathedral. At the welcoming on the airport he stated that:

“Personally, I have always believed that visiting my Fatherland under these historic circumstances is dictated not only by my heart’s desire, but also by my sense of duty as the Bishop of Rome. I believe, that I should be with my Countrymen in this sublime – and difficult moment in the history of our Fatherland. […] Peace be with you, Poland! My Fatherland!”3

During his second pilgrimage to the Fatherland, the pope’s homilies showed his perfect knowledge on Polish affairs and a precise judgement of the then current problems. Hence, there are many references to the ideals of the August 1980 and to moral renovation. Only moral victory can lead the society out of the decay and bring back its unity4 – he reminded in the homily during the Holy Mass at the 10th-Anniversary Stadium with three hundred thousand faithful present.

“And even though life in our Fatherland, since December 13th 1981, has been under the harsh rigor of the martial law […] – I have not stopped trusting that the social renovation, which was promised many times, according to the rules worked out in such difficulties in the ground-breaking days of August 1980 and included in agreements, will systematically come to life.”5

- he said during his meeting with the authorities of the Polish People’s Republic at the Belweder palace.

In Katowice, he stressed the value of human work and social justice. He emphasized, that a working man is not a tool for production, but a person; a person, who has priority over the capital during the entire production process6. At Jasna Góra, he recalled the words he said there in 1979: here, we have always been free7.

The pope spoke about Poles and for Poles. And when in 1983 he came to Poland which was still under the martial law, he came as a comforter, someone, who wanted to bring back hope and show unity with those who were suffering in any way.

The words spoken by saint John Paul II during the pilgrimages to the Fatherland are for Poles the most substantial and meaningful. Even these tough ones, like - when in 1991 – the pope almost shouted at Poles when he came to the free Poland after the fall of the Polish People’s Republic and spared no bitter, and even harsh words.

“One cannot create a fiction of freedom, which seemingly liberates people, but in reality enslaves and demoralises them. We need to make the examination of conscience at the brink of the Third Republic of Poland! – he raised his voice firmly. – Maybe I’m talking the way I’m talking, because this is my Mother, this land. It is my Mother, this Homeland […]. Understand, that these matters cannot not pain me! They should pain you to. It is easy to destroy, it is much harder to rebuild.”8

John Paul II cared for Poles to use their regained freedom well.

Through the entire pontificate of saint John Paul II, he deepened and widened his understanding of love towards the Fatherland. As he wrote in the book Memory and identity: Father is the one, who along with mother gives life to a new human being. With the birth from father and mother, a term of patrimony is connected, which is the background for the term “Fatherland”11.

He criticised life according to body, the cause of the ethical and moral crisis and leads to the development of anti-civilisation. He was against consumerism: money, wealth and other conveniences of the world will pass, so they cannot be our ultimate goal9. He criticised relativism and spreading lies – also by the media.

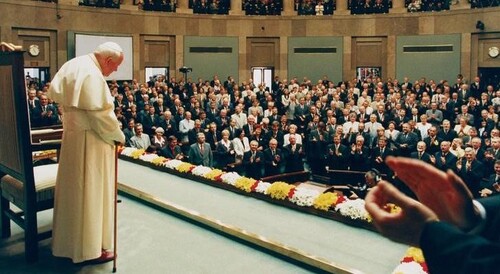

For sure, without precedence remain the words of the Polish pope spoken at the Polish parliament in 1999. After all, for the first time in Poland’s history and in the history of the world, the Holy Father made a speech directed at MPs and senators. He thanked the Lord of history for […] the shape of Polish changes, but he also warned against democracy making an alliance with ethical relativism, since democracy without values can easily transform into open or camouflaged totalitarianism. He also reminded that

“executing political power, either in a commonwealth or in institutions representing the state, should be a faithful service to the man and society, not seeking personal or group profits bypassing the well-being of the entire nation.”10

With such a strong, firm address, the pope’s promise that Poles and Poland had a special place in his heart rang true. And it was not only the sign of huge nostalgia or sentimentalism. For John Paul II, Fatherland was not an abstract term.

Patriotism according to John Paul II

Through the entire pontificate of saint John Paul II, he deepened and widened his understanding of love towards the Fatherland. As he wrote in the book Memory and identity: Father is the one, who along with mother gives life to a new human being. With the birth from father and mother, a term of patrimony is connected, which is the background for the term “Fatherland”11.

In the pope’s understanding of the Fatherland and Nation there are hidden sources which explain the truth in the words: fatherland – father; nation – nat [from Latin – born; translator’s annotation]; to give birth, family12. This take allowed the pope for a clear reference of the Fatherland to the Gospel, where the word “Father” is essential after all.

However, John Paul II did not stop at fatherhood itself. He pointed out that in the Bible the Father brings the world special patrimony, extraordinary heritage, although He does so with the help of a woman, who is a mother:

“Entire Christianity, in its universal dimension, is the patrimony where Mother’s role was very substantial”.

And it was the Homeland which was a mother for the pope. He talked about it directly i.e. in Kielce, where he went during his fourth pilgrimage to Poland in 1991.

The fact that patriotism was not an abstract term for the pope is best exemplified by the fact that he applied it to theology and connected it to the Ten Commandments. As the fourth commandment orders to respect the father and mother, the same commandment requires care for the Homeland. The pope explicitly said that patriotism has moral value and that it falls under the fourth commandment which obliges us to respect our father and mother13.

!["My beloved Fatherland, Poland, […] God exalts you and marks you as special, but know how to be grateful!” <i>With these words from the Journals of Sister Faustyna I want to say goodbye to you, dear brothers and sisters, my fellow countrymen! My entire soul turns to the Fatherland.</i> Fragment of a farewell speech of John Paul II during his last, VIII trip to the Fatherland (2002). In the picture the consecration of the temple of Divine Mercy in Cracow-Łagiewniki](/dokumenty/zalaczniki/166/mini/166-130436_m.jpg)

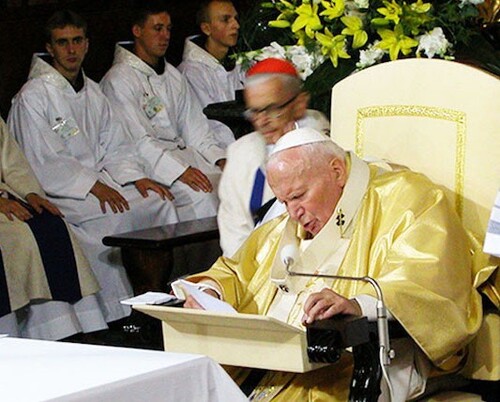

"My beloved Fatherland, Poland, […] God exalts you and marks you as special, but know how to be grateful!” With these words from the Journals of Sister Faustyna I want to say goodbye to you, dear brothers and sisters, my fellow countrymen! My entire soul turns to the Fatherland. Fragment of a farewell speech of John Paul II during his last, VIII trip to the Fatherland (2002). In the picture the consecration of the temple of Divine Mercy in Cracow-Łagiewniki

This way of thinking about the love for the Fatherland enables us to more deeply understand when someone devotes their whole life for it or makes sacrifices. It also allows us to better understand the motivation behind the actions of many patriots in Polish history, i.e. pr. Ignacy Skorupka and beatified pr. Jerzy Popiełuszko. Their need to act came from patriotic reasons, but understood in a deeper, evangelic perspective.

May the spirit of mercy, brotherly unity, agreement and cooperation and authentic care for the well-being of our Fatherland. I hope that through caring for these values, the Polish society, which for centuries have belonged to Europe, finds its place among the structures of the European Commonwealth. Fragment of a farewell speech of John Paul II during his last, VIII trip to the Fatherland (2002). In the picture the pope prays at Kalwaria Zebrzydowska.

After all, John Paul II often spoke about it in this context, like in June 1999, when he blessed the Home Army memorial in Warsaw or when he visited the cemetery of heroes of the Battle of Warsaw in Radzymin and reminded about Poles’ duty to honour the memory of the heroism of their ancestors.

Finally, the love for the Fatherland and patriotism of John Paul II also include the love for his nation’s culture. The national heritage for the pope is also the spiritual heritage, national culture and tradition.

Saying goodbye to Poland, I want to send my best wishes to all of you, dear compatriots. So many waited for me, so many wanted to meet me. Not all were able to do so. Fragment of a farewell speech of John Paul II during his last, VIII trip to the Fatherland (2002). In the picture the faithful (over a million) gathered for the Holy Mass at the Cracow fields.

I am a son of the Nation – he said – which survived the harshest events in history, which was doomed to perish by its neighbours countless times – and yet stayed alive and remained itself. It retained its own identity and, among partitions and occupations, kept its sovereignty as a Nation – taking as its groundwork not any means of physical power, but its own culture, which in this case turned out to be mightier than the foreign powers.14

Patriotism for the pope was also caring for culture, but first and foremost caring for language, which allowed for conveying the truth about the world and the truth about himself, as well as communicating with others – which serves to exchange thoughts and better learn the truth, and by doing so deepen and strengthen personal identity. Language helps express culture, which is the condition for the existence of a nation.

In the context of love to Poland, the pope also invoked the great works of Polish belles-letters, including Mikołaj Rej and Jan Kochanowski, the most famous literary pieces of the XIX century, the works of great romantic poets: Adam Mickiewicz, Juliusz Słowacki, Zygmunt Krasiński, Cyprian Kamil Norwid. He stressed many times, that it was the Polish culture which allowed his Homeland to regain independence in 1918.

Patriotism is not only loving what’s native, loving history, tradition, language or the native landscape, but also love for the works of one’s compatriots and the fruits of their genius15. In this context, the pope was referring, in Gniezno in 1979, to the Polish religious song – Bogurodzica, reminding that it is the oldest memorial for Polish literature, at the same time arguing that it is not only a song, but also the declaration of faith, a Polish symbol, a Polish Credo […]. The main creeds and moral rules are embedded on it16. In the book Memory and identity, John Paul II added that Bogurodzica became the national anthem which already at Grunwald led the Polish and Lithuanian ranks to fight against the Teutonic Order.17

In the context of love to Poland, the pope also invoked the great works of Polish belles-letters, including Mikołaj Rej and Jan Kochanowski, the most famous literary pieces of the XIX century, the works of great romantic poets: Adam Mickiewicz, Juliusz Słowacki, Zygmunt Krasiński, Cyprian Kamil Norwid. He stressed many times, that it was the Polish culture which allowed his Homeland to regain independence in 1918.

It is clear that the term “Fatherland” includes a very deep coupling between what’s spiritual and material, between culture and land18 — he said. When thinking on Norwid’s words, he reminded many times: Fatherhood is a great collective duty19, and that is why in his speeches to his compatriots he often referred to literary works which showed the heroic attitudes of Poles fighting to regain the country’s freedom, capable of the greatest sacrifices in the name of their love for her and a well-understood patriotism.

In this context, it is obvious that the pope noticed an unbreakable bond between the terms patriotism and nation. He explicitly wrote in the book Memory and identity: the Nation and Fatherland remain realities which are irreplaceable.20

It is also worth mentioning that the term of the Fatherland was close to pope’s heart since the time of his youth. When he was still a cardinal, Karol Wojtyła wrote in his poem Thinking Fatherland from 1974:

Fatherland – when I think – then I express and root myself,

my heart tells me about it, like a hidden border, which goes through me to others,

to take all of us into the past older than any of us:

I come from it… when I think Fatherland – to hide it in me like a treasure.21

One needs to invoke his words again: Poland, know how to be grateful!

The article comes from issue no. 10/2018 of the “Biuletyn IPN”

1 Apel Jana Pawła II do gen. Jaruzelskiego, 18 grudnia 1981 roku, o powrót do pokojowego dialogu władzy ze społeczeństwem i zaprzestanie rozlewu krwi, [w:] Jan Paweł II, Prymas i Episkopat Polski o stanie wojennym. Kazania, listy, przemówienia i komunikaty, Londyn 1982, s. 69–70; por. P. Raina, Kościół w PRL. Kościół katolicki a państwo w świetle dokumentów 1945–1989, t. 3: Lata 1975–89, Londyn 1982, s. 254.

2 Apel Jana Pawła II…, s. 70.

3 Jan Paweł II, Przemówienie Ojca Świętego wygłoszone na lotnisku Okęcie, Warszawa, 16 VI 1983 r., [w:] Jan Paweł II w Polsce 1979, 1983, 1987, Warszawa 1989, s. 284–285.

4 Jan Paweł II, Homilia Ojca Świętego wygłoszona podczas Mszy św. odprawionej na Stadionie Dziesięciolecia, Warszawa, 17 VI 1983 r., [w:] Jan Paweł II w Polsce..., Warszawa 1989, s. 321.

5 Jan Paweł II, Przemówienie Ojca Świętego wygłoszone podczas spotkania z władzami PRL w Belwederze, Warszawa, 17 VI 1983 r., [w:] Jan Paweł II w Polsce..., Warszawa 1989, s. 300.

6 Jan Paweł II, Przemówienie Ojca Świętego wygłoszone po Mszy św. odprawionej na lotnisku w Muchowcu, Katowice, 20 VI 1983 r., [w:] Jan Paweł II w Polsce..., Warszawa 1989, s. 414.

7 Jan Paweł II, Homilia Ojca Świętego wygłoszona podczas Mszy św. odprawionej na Jasnej Górze, Częstochowa, 19 VI 1983 r., [w:] Jan Paweł II w Polsce..., Warszawa 1989, s. 366.

8 Jan Paweł II, Homilia Ojca Świętego wygłoszona podczas Mszy św. odprawionej na lotnisku w Masłowie, Kielce, 3 VI 1991 r., „L’Osservatore Romano” 1991, nr specjalny, s. 38.

9 Jan Paweł II, Homilia Ojca Świętego wygłoszona podczas Mszy św. odprawionej na stadionie OSIR-u, Płock, 7 VI 1991 r., „L’Osservatore Romano” 1991, nr specjalny, s. 82.

10 Jan Paweł II, Przemówienie Ojca Świętego wygłoszone w parlamencie RP, Warszawa, 11 VI 1999 r., [w:] Jan Paweł II, Polska 1999. Przemówienia i homilie, Warszawa 1999, s. 108.

11 Jan Paweł II, Pamięć i tożsamość. Rozmowy na przełomie tysiącleci, Kraków 2005, s. 74.

12 G. Ryś, Ojczyzna i naród w nauczaniu Jana Pawła II, [w:] Aspekt wychowawczy umiłowania Ojczyzny i Narodu w myśli Papieża Jana Pawła II. Materiały XVII Ogólnopolskiego Forum Szkół Katolickich, Częstochowa 2006, s. 37.

13 Jan Paweł II, Pamięć i tożsamość…, s. 71.

14 Jan Paweł II, Przemówienie Ojca Świętego wygłoszone w siedzibie UNESCO, Paryż, 2 VI 1980 r., [w:] Jan Paweł II, Nauczanie papieskie, 1980, t. III, 1, Poznań – Warszawa 1985, s. 732.

15 Jan Paweł II, Pamięć i tożsamość…, s. 71–72.

16 Jan Paweł II, Przemówienie Ojca Świętego wygłoszone podczas spotkania z młodzieżą, Gniezno, 3 VI 1979 r., [w:] Jan Paweł II, Nauczanie papieskie, 1979, t. II, 1, Poznań 1990, s. 611.

17 Jan Paweł II, Pamięć i tożsamość…, s. 88.

18 Ibidem, s. 67.

19 C.K. Norwid, Memoriał o młodej emigracji, [w:] idem, Pisma wybrane, t. 4, oprac. J.W. Gomulicki, Warszawa 1968, s. 451.

20 Jan Paweł II, Pamięć i tożsamość…, s. 73.

21 K. Wojtyła, Myśląc Ojczyzna, [w:], idem, Poezje i dramaty, Kraków, 1987, s. 92.