The Polish Ministry of Foreign Affairs responded to this provocation with a harsh diplomatic note. The Poles’ indignation is very understandable. At the necropolis where Polish officers shot by the NKVD in 1940 are commemorated, an exhibition commemorating the victims of an entirely different war who died and were buried hundreds of kilometres away from Katyń was organised. What’s even more important, is the fact that those Red Army soldiers, in contrast to the victims of Katyń, were not shot in Poland but died due to an epidemic or hunger. (There was a high probability of death due to starvation and diseases also in the case of soldiers who weren’t captured by Poles but remained in the Red Army, due to a great economical chaos in the Soviet Russia at the time).

We are, therefore, dealing here with an attempt to bring back the theory from the late Soviet era, according to which Joseph Stalin wanted to avenge the death of the Soviet POWs in Polish captivity between 1920-1921 when he ordered the murder of Polish officers in Katyń. In reality, when Stalin ordered the killing in spring 1940 he didn’t have the fate of the Red Army soldiers in mind at all. Soldiers taken into captivity – as the events of the Second World War showed – were nothing else but traitors of the nation to him. The reason for the Katyń Massacre was probably the fact that in the summer of 1940 Stalin intended to attack Germany. In this situation, the Polish government-in-exile would become his potential ally and he would have to free the arrested Polish officers and enable the creation of a new, Polish army. However, this army wouldn’t be subordinate to the USSR and Stalin wanted to have the military completely under his control. That is why he decided to immediately eliminate the Polish officers.

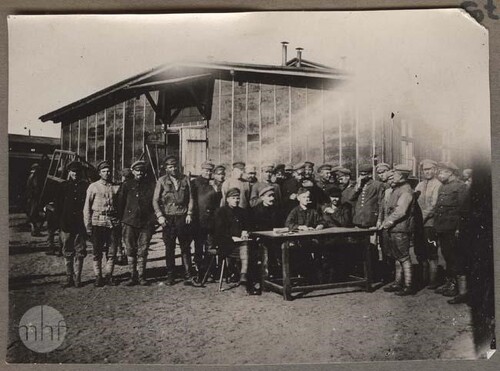

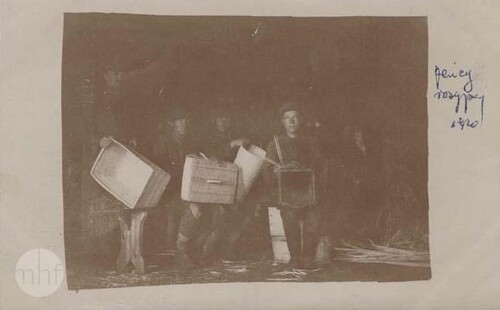

Polish-Bolshevik war. The questioning of a Red Army prisoner by soldiers of the Polish Siberian Brigade. From the collections of the National Digital Archives

At the necropolis where Polish officers shot by the NKVD in 1940 are commemorated, an exhibition commemorating the victims of an entirely different war who died and were buried hundreds of kilometres away from Katyń was organised. What’s even more important, is the fact that those Red Army soldiers, in contrast to the victims of Katyń, were not shot in Poland but died due to an epidemic or hunger.

Inflated numbers

To this day, opinions are spread in Russia that 60, 80 or even 100 thousand people supposedly died in the Polish captivity between 1920-1921. This last number was given by the Russian Minister of Culture Vladimir Medinsky3. His method of counting was rather simple. For the starting point he used the maximum estimated number of the Soviet prisoners: 157 000, 165 550, 206 877 or 216 000 and then subtracted the number of those who returned home from captivity – 67 000. That way, he came up with the result of 100 thousand victims or more. Historian Gennadiy Matveev in turn estimates the mortality among the prisoners in Polish captivity at 25-28 thousand people. Based on the documents of the Polish general command from the years 1919-1920 he came to the conclusion that during twenty months 206 877 Red Army soldiers were captured, out of which only 157 thousand were actually handed to the ministry of military affairs and classified as prisoners of war.4 However, both those numbers are highly inflated: 206 877 prisoners is one and a half more than the number of soldiers who fought in the ranks of the Soviet Western Front on the eve of the Battle of Warsaw (130-150 thousand people); at the same time it is worth stressing that these were the estimates of Józef Piłsudski who had no reason in the slightest to lower the numbers of the Soviet troops.5 The definite majority of prisoners was taken to captivity during the Battle of Warsaw and later, although they were mainly the front line soldiers as the back of the army, stretching all the way to Minsk, already managed to disperse. Apart from that, more than 40 thousand soldiers of the Western Front were interned in Eastern Prussia. The number 206 877 was the result of adding all the reports of various units and subunits of the Polish forces and the number of prisoners was inflated by them regularly. The difference between the total number of prisoners and those who ended up in POW camps, at 50 thousand people, is also highly improbable. This many people couldn’t have joined the ranks of the armies of Symon Petliura and Stanisław Bułak-Bałachowicz which, at the end of the war, counted much less than 50 thousand soldiers.

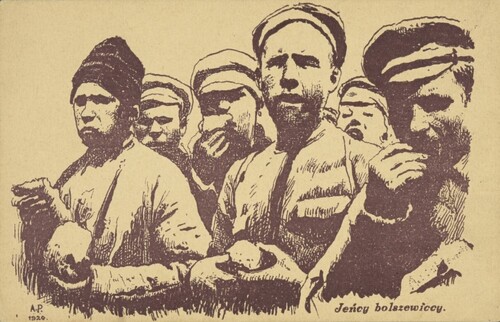

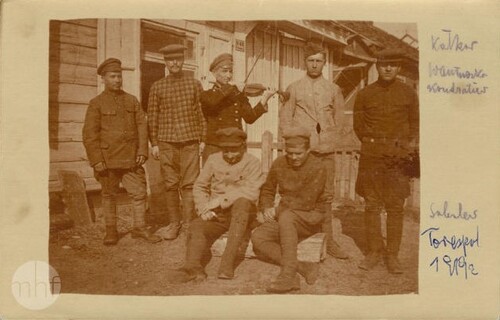

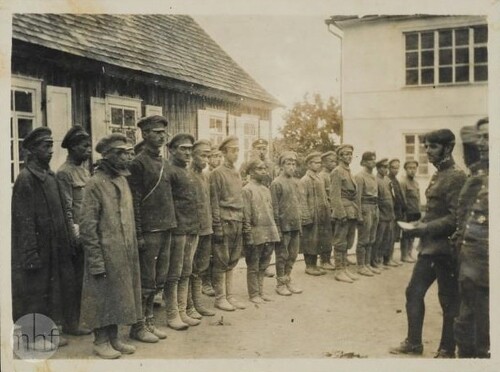

Polish-Bolshevik war. A group of Red Army POWs. From the collections of the National Digital Archives

How many Red Army soldiers died in the Polish captivity?

According to Soviet data, not 67 thousand but 75 699 prisoners returned.6 Almost all of them were captured in 1920. Apart from that, in August and September of the same year, after the defeat near Warsaw, around 43 thousand Soviet soldiers were interned by the German authorities in Eastern Prussia. How many of them died during the interning – it is not exactly known, although the number was probably not high as 40 986 people were released in the middle of 1921, and some of them had returned to their homeland before that.7 The death rate among those interned by the Germans was much lower than the mortality of the Red Army soldiers in Polish captivity. It can be explained by lighter conditions and shorter time of captivity in case of the interned, as well as with the fact that there were no mass epidemics in Germany at the time. Despite the blockades put on the country by the Entente, Germany suffered less because of the war than Poland, which became the arena of bloody fights during the First World War, ever did.

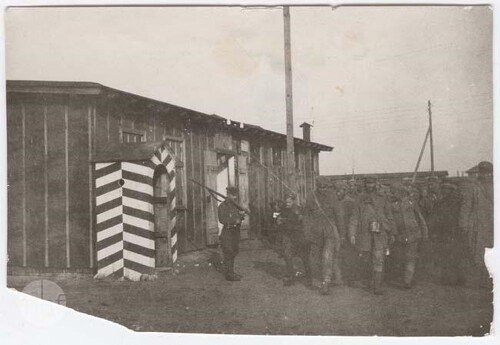

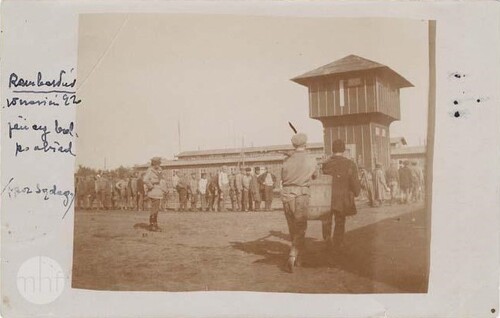

A column of Russian prisoners, 1920. Author: photographer Jan Zimowski. From the collections of the Museum of the History of Photography in Cracow

From the total number of Soviet prisoners who ended up in Polish captivity, between 16 to 18 thousand died, mainly due to an epidemic. Around 25 thousand former Red Army soldiers joined the army of the Ukrainian People’s Republic, Boris Savinkov’s and Bułak-Bałachowicz’s troops or other anti-Bolshevik formations, while following the truce and the Peace of Riga a definite majority of them remained in Poland or left to other countries of Europe.8

To this day, opinions are spread in Russia that 60, 80 or even 100 thousand people supposedly died in the Polish captivity between 1920-1921. This last number was given by the Russian Minister of Culture Vladimir Medinsky. Historian Gennadiy Matveev in turn estimates the mortality among the prisoners in Polish captivity at 25-28 thousand people. However, both those numbers are highly inflated.

If we were to add all the Polish data on the records of Soviet prisoners, divided into specific war operations, we would get the number of 118.3 thousand people. That way, 7096 soldiers were captured in 1919; 30 thousand – during the Kiev operation in April and May 1920; 41 161 – during the counteroffensive near Warsaw in August and September 1920; 40 thousand – during the last fights since September 11th to October 18th 1920.9 Apart from that around a thousand Soviet prisoners died already in 191910, and at least 7 thousand were freed during the Red Army’s counteroffensive at the south-western front in May and June of 1920.11 Adding it all together, we are left with the number 112.3 thousand prisoners, out of which 104.2 thousand were captured in the year 1920 – which is 9.3 thousand more than the official number of MIAs in 1920 at the western and south-western front lines.12 It is probably that number – 112.3 thousand prisoners – which is the closest to truth. If it is, then the number of prisoners who remained in Poland or other countries after the peace treaty could be estimated at 19.6-20.6 thousand people.

Polish-Bolshevik war. A group of Red Army POWs. From the collections of the National Digital Archives

Our estimations are concurrent with the estimates of a Polish historian, Zbigniew Karpus who states that after the fighting had stopped in the middle of October 1920 there were around 110 thousand Soviet prisoners in Poland, including around 50 thousand captured during the Battle of Warsaw since the beginning of August to September 10th; 40 thousand – since September 11th to October 18th, and 15-20 thousand captured in the time period between February 1919 to July 1920. Among those, no less than 25 thousand soldiers joined the Russian or Ukrainian troops which were allied with Poland, 16-18 thousand died and we already know – thanks to the efforts of the Polish side – around 12 thousand names of those, and around 67 thousand were returned to their homeland.13 Close to 8 thousand Soviet prisoners died in a POW camp in Strzałków, nearly 2 thousand in Tuchola and 6-8 thousand in other camps. Perhaps the discrepancy between the number of prisoners who were returned to their homeland given by the Soviets and the number given by Poles came from the fact that the Soviets included in their estimations those prisoners who were freed by the Red Army during the June and July counteroffensive in 1920. Meanwhile, according to the Soviet documents the total number of MIAs at the western and south-western fronts added up to 94 880, while there were supposedly 12 730 less of them at the south-western front than the western one, even though Poles captured most of the prisoners at the western front.14 It underlines the fact that the Soviets significantly lowered their losses, especially at this front line.

From the total number of Soviet prisoners who ended up in Polish captivity, between 16 to 18 thousand died, mainly due to an epidemic. Around 25 thousand former Red Army soldiers joined the army of the Ukrainian People’s Republic, Boris Savinkov’s and Bułak-Bałachowicz’s troops or other anti-Bolshevik formations.

The death toll of diseases

The Red Army counted 4 424 317 soldiers on June 1st, 1920.15 In the course of this year, 208 519 of them died due to contagious diseases.16 This means, that epidemics lowered the number by 4.7 percent. Another 39.3 thousand, 0.9 percent, died due to tragic accidents and other illnesses. In the Polish captivity, even if we assume the highest number of 18 thousand dead prisoners, the mortality rate wasn’t much higher – 15.2 percent. From the above statistics, it is clear that from among the 18 thousand Red Army soldiers who died in Polish captivity, 6.3 thousand would have perished even if they weren’t captured but were still among the ranks of the Red Army.

Suffice to say, Polish captivity was definitely not a vacation for the Red Army soldiers, especially in light of the economical crisis in the country. However, the Polish authorities never partook in a deliberate extermination of the Soviet prisoners. That is the major difference between the events of the Polish-Soviet war in 1920 and the Katyń executions without trial.

Article in Polish was translated from Russian by Jerzy Szokalski

The article comes from issue no. 7-8/2017 of the “Biuletyn IPN”

1 Polsza wozmutiłaś informacyjej o krasnoarmiejcach w Katyni, „Sputnik”, 8 IV 2017 r., https:// ru.sputniknewslv.com/world/20170408/4401347/Polsza-Katyn-memorial-krasnoarmejcy-MID. html [dostęp: 30 VI 2017 r.].

2 Por. B. Sokołow, Prawdy i mity Wielkiej Wojny Ojczyźnianej 1941–1945, Warszawa 2017, s. 64–65.

3 W. Miedinskij, Kuda isczezli 100 tysiacz plennych krasnoarmiejcew?, „Komsomolskaja Prawda”, 10 XI 2014 r., http://www.kp.ru/daily/26305.5/3183560/ [dostęp: 30 VI 2017 r.].

4 G. Matwiejew, U polakow takoje że impierskoje myszlenije, czto i u ruskich, 2 III 2015 r., https://lenta.ru/articles/2015/03/02/poland/ [dostęp: 30 VI 2017 r.]; G. Matwiejew, W. Matwiejewa, Polskij plen. Wojennosłużaszczije Krasnoj armii w plenu u polakow w 1919–1921 gg., Moskwa 2011, s. 43.

5 M. Tuchaczewski, Pochod za Wisłu; J. Piłsudski, Wojna 1920 goda, Moskwa, s. 105.

6 Rossija i SSSR w wojnach XX wieka. Potieri woorużonnych sił. Statisticzeskoje issledowanije, red. G. Kriwoszejew, Moskwa 2001, s. 128.

7 Ibidem.

8 Z. Karpus, W. Rezmer, Priedisłowije polskoj storony, [w:] Krasnoarmiejcy w polskom plenu w 1919–1922 gg. Sbornik dokumientow i matieriałow, Moskwa 2004, s. 24.

9 D. Lipińska-Nałęcz, T. Nałęcz, Naczało, [w:] Biełyje pjatna. Czornyje pjatna. Słożnyje woprosy w rossijsko-polskich otnoszenijach, red. A. Torkunow, A. Rotfeld, Moskwa 2010, s. 70.

10 Z. Karpus, W. Rezmer, Priedisłowije polskoj storony, [w:] Krasnoarmiejcy w polskom plenu…, s. 20.

11 G. Matwiejew, Priedisłowije rossijskoj storony, [w:] Krasnoarmiejcy w polskom plenu…, s. 14–15.

12 Rossija i SSSR…, s. 124, tab. 64.

13 Z. Karpus, Russkije i ukrainskije wojennoplennyje i internirowannyje w Polsze w 1918–1924 godach, tłum. Z polskiego, Toruń 2002, s. 70–72, 147–148.

14 Rossija i SSSR…, s. 124, tab. 64.

15 Ibidem, s. 117, tab. 59.

16 Ibidem, s. 131, tab. 167.