In the spring of 1944, the commander of the Warsaw Division of the Home Army gave the operational order describing not only the targets of attacks of main forces in the upcoming Warsaw Uprising, but also the tasks of the healthcare for the time of the fighting. Medical equipment and bandages were prepared before the “W” hour, but only for three days of fighting instead of 63, and that’s how long it lasted.

There was also a shortage of doctors and nurses who could treat the wounded. In the later stages of fighting, the condition of field hospitals was terrible. Surgeries were conducted without anaesthetics, with candles or oil lamps as lighting and without proper hygiene.

Wounded Polish soldiers and civilians lied on the floors, in darkness, in the stench of sweat and festering wounds, and they died without proper help.

A tragic fate

The occupier destroyed entire parts of the city one by one, including field hospitals, which were often located in random places like basements, private apartments, church basements, stores and warehouses, among others, in the Old Town — in the Raczyńscy Palace on the Długa 7 Street or at the headquarters of the Philanthropic Association on Freta 10.

The Germans did not follow the articles of the Geneva Convention, nor did they respect the emblem of the Red Cross. Wounded civilians, soldiers, and the medical staff were often the victims of brutal killings. Usually, only the slightly injured survived, as well as the medical personnel which was ordered to leave the hospitals. Then, the Germans set the buildings on fire, with living people inside.

There were also more than 200 of the so-called first aid points during the uprising. They usually had several beds and provided help for those with minor wounds.

It is also important to mention the permanent hospitals which operated in Warsaw during that time. 20 medical facilities functioned before the “W” hour. Unfortunately, these also weren’t spared by the Germans. The enemy soldiers would go into them and order the personnel and less injured to leave the buildings in 5 to 10 minutes. Those who remained were murdered on site.

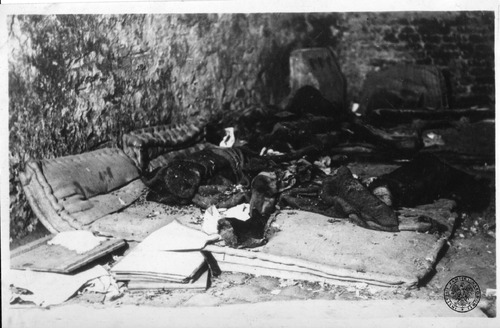

The remains of people murdered in hospitals during the uprising were later exhumed and buried in Warsaw cemeteries.

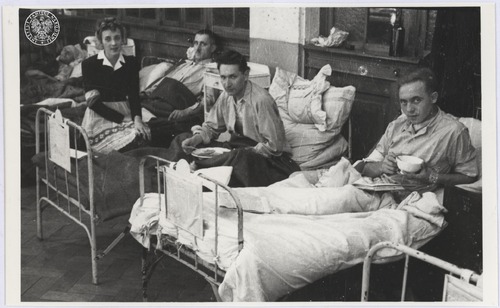

Field hospital on Złota 22 Street. Author: Henryk Śmigacz. Photo from the album with pictures from the Warsaw Uprising and after the war, which is part of Henryk Śmigacz’s private archives, acquired by the Institute of National Remembrance as part of the project The Archive Full of Remembrance (Photo from the collections of the Institute of National Remembrance)

Signs of sacrifice

There are photographs stored in the archives of the Institute of National Remembrance showing the hard work of the uprising’s field hospitals. They were taken by the Eugeniusz Lokajski, codename “Brok”. One such picture shows the field hospital at the Mokotowska Street. Another photograph shows nurse Janina Stęczniewska, codename “Inka”, who was in the Female Military Service. The picture was taken in the field hospital of the “Koszta” Company, in the building of the former Insurance Association on Marszałkowska 124/128 Street. We can see her with her young daughter, Hania, next to Edmund Michniewski, codename “Miś, who got wounded on August 4, 1944, at the Wronia Street. It is worth adding that the woman survived the uprising, and ended up in Cracow with the wounded after the uprising surrendered.

Another photograph of the Institute’s archives was taken by Jerzy Tomaszewski, codename “Jur”, and shows a nurse leaning over a sick person in the field hospital in the headquarters of the PKO bank, on the Świętokrzyska Street.

There are also more than a dozen pictures in the collections of Henryk Śmigacz, who was taking them on the order of the Government Delegation for Poland, showing the field hospital of the “Gurt” Group in the northern Śródmieście district, on Złota 22 Street, which was located in the building of the Office of Scales and Measures. In one of the pictures we can see a nurse next to lying men. We can see the uprising’s armband on her arm.

Leonard Sempoliński registered the proof of the Germans’ brutality, as in April 1945 he took the pictures of the remains of those murdered on September 2, 1944, in the hospital on Długa 7 Street.