On March 1, 1951, oppressors of the communist regime, installed west of the Bug river by Moscow in 1944, murdered the leaders of the 4th General Board (ZG) of the Freedom and Independence Association (WiN), chairman Łukasz Ciepliński and his six subordinates: Adama Lazarowicz, Mieczysław Kawalec, Józef Rzepka, Franciszek Błażej, Józef Batory and Karol Chmiel.

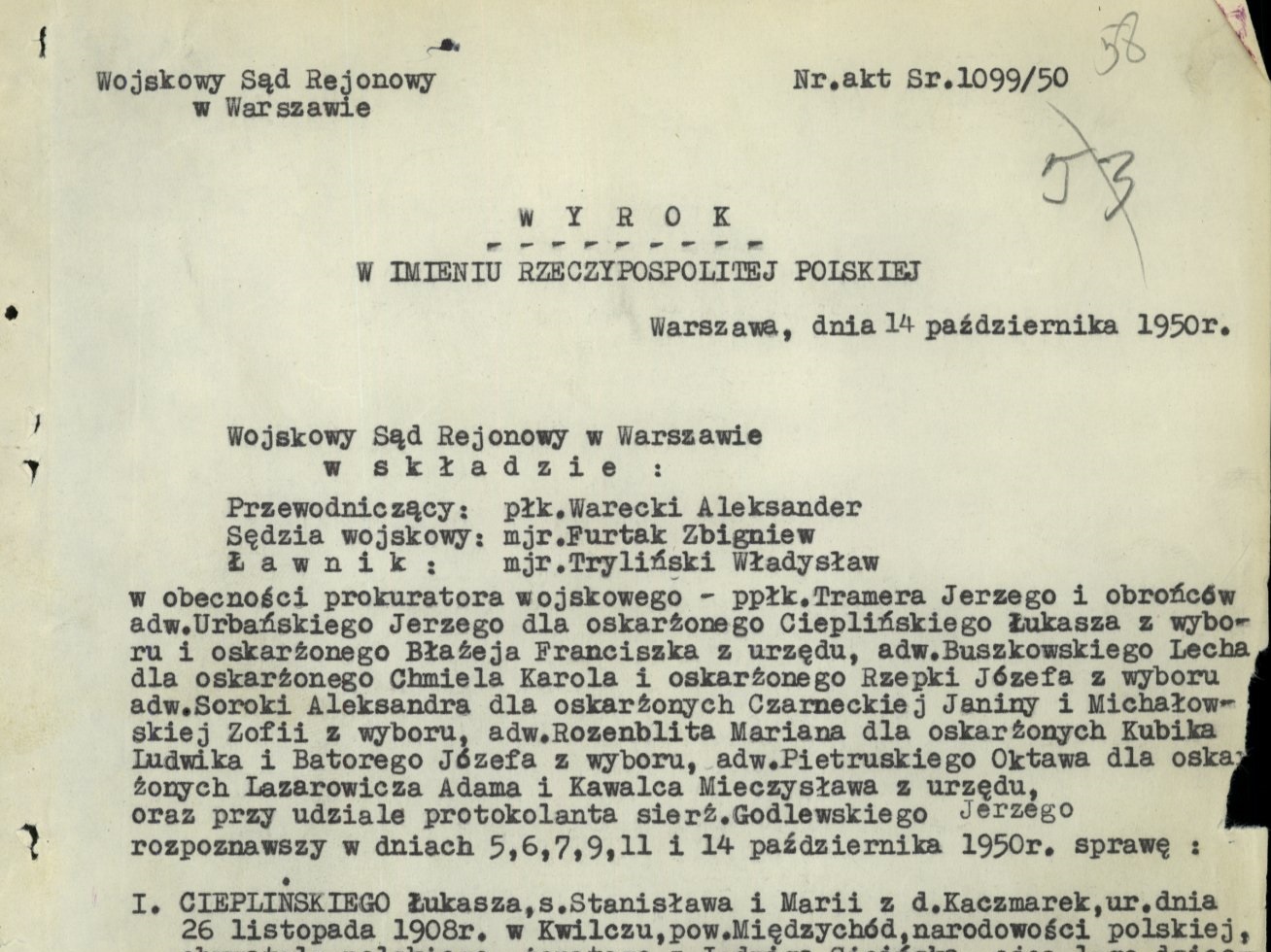

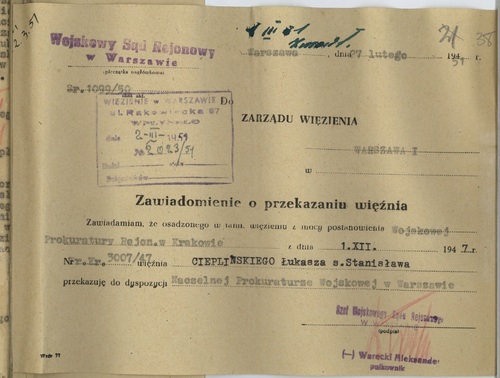

Under the conditions of the de facto Soviet occupation of Poland this murder was inevitable, but even still the communist tyranny, similarly to the Nazi regime, kept up the appearances of formality. This scenography of the state of law was meant to legitimise the killing of people who not only had great achievements, but were also completely innocent. In the case of the members of the 4th General Board of WiN, who were officers of the Polish Army with many contributions in the war for Polish independence, there was a trial held in 1950 at the Martial Regional Court in Warsaw. Colonel Aleksander Warecki headed the adjudicating panel in this case.

In the archives of the Institute of National Remembrance, there are materials which allow us to see the measure of men like Łukasz Ciepliński and Aleksander Warecki. It also helps us understand why us, Poles, need such a holiday, celebrated on March 1, in the first place.

Hunt them down with no mercy

Warecki, leading the judicial murder on members of the 4th General Board of WiN, was a completely devoted official of the communist regime. But he was not a mindless puppet. Before the war, he studied law at the Jagiellonian University and later practiced in the Cracow office of his rich father, Leon Warenhaupt. He then served the Soviet occupants of Poland with a fanatical devotion. He was more of a legal craftsman than an artist; he understood that it was not excellence which was desired by the communists, but rather a blind following of party orders. And so he worked his way up the chain of the communist, martial judiciary. He began at the frontline martial courts, spend time as the head of the Martial Regional Court in Wrocław and Warsaw, to then finally reach positions in the Board of Martial Courts.

In October, 1948, Colonel Władysław Garnowski, the president of the Supreme Martial Court, wrote this in his service review of Warecki:

“In the more demanding cases, e.g. concerning acts of sabotage or criminal political ties, he often leads by example with the understanding of the ongoing war of classes. He is politically secure. He has firm democratic tendencies and correctly sees the role of the USSR in the ongoing fight against imperialism.”

He was rewarded and awarded on many occasions, also financially. The regime recognised his eagerness “on the frontlines of the fight against the class enemy”, and he repaid it in the courtrooms by issuing draconian punishment for heroes of the 1st and 2nd underground resistance. He issued nearly 40 death sentences, but this toll is incomplete — he often told subordinate judges what sentences to hand out, including death penalties. His orders were followed to the letter.

Aleksander Warecki in the rank of a colonel in October, 1950, when as the lead judge of the Military District Court in Warsaw he sentenced Łukasz Ciepliński, Adam Lazarowicz, Mieczysław Kawalec, Józef Rzepka, Franciszek Błażej, Józef Batory and Karol Chmiel to death. Photo from the archives of the Institute of National Remembrance

The so-called judicial bench led by Aleksander Warecki, which gave the ultimate punishment to Łukasz Ciepliński, used the following words to justify their ruling:

“Based on a deep analysis and after considering all facts of the case, the Court finds that the accused Mr. Ciepliński deserves only the highest punishment - the death penalty. The string of crimes committed by the accused against his own nation and homeland, against the best sons of the Polish People[,] against the heritage of the people’s masses of the Reborn Poland is so grave that there is no counterweight to his sins and crimes.”

In this way Warecki was showing his “unconditional devotion to the People’s Poland”, which he emphasised in his resume written in 1948.

In 1956, when the then leadership of the Polish United Workers’ Party decided to hold a sham reckoning (still very partial and limited to single officers) towards the communist criminals active after 1944, Warecki was also asked about his “work” as a judge. He left no room for doubt whether he had any problems with his conscience whatsoever by openly saying:

“We in the regional courts were faced then (…) with the task of fighting those who rose against the people’s power (…) I was deeply convinced of the righteousness of these theses and to this day I believe they were right.”

Aleksander Warecki, a communist criminal, never faced any punishment. He died in 1986 as a respected, Warsaw lawyer. His grave is at the Military Powązki Cemetery, in Poland’s capital.

I did not know hatred

When in September 1939 Łukasz Ciepliński stood in defence of Poland as the soldier of the Polish Army, he probably didn’t imagine that he would give eight years of his young life to this fight. From fighting in the defence of the country in 1939, through commanding a large, strong and incredibly active Rzeszów Inspectorate of the Home Army, with which he liberated the Podkarpacie province in 1944 under Operation Tempest, until leading the 4th General Board of the Freedom and Independence Association, he had always believed, as he wrote in one of the secret messages in the communist prison, that:

“Poland will regain its independence, and the man will get back his shamed dignity.”

Just as he could not come to terms with the German occupation he rejected any compromise with the new, Soviet occupant. He continued the fight for Poland in the structures of the “NIE” organisation, created after the dissolution of the Home Army. He then served in the Armed Forces Delegation for Poland, and finally in the Freedom and Independence Association, where he commanded the Southern Area. Between 1946 and 1947, under the extremely difficult conditions, he took upon himself the responsibility for the entire organisation which had goals and ambition on a national scale: he became the Chairman of the 4th and last General Board of the Freedom and Independence Association.

After he got arrested by the Security Office in November, 1947, Łukasz Ciepliński went through a brutal questioning. An additional torture for him was the fact that he had to spend almost three years in jail until his sham trial. He wrote this in one of the secret letters to his wife:

“I thought they would allow me to see you at the trial, so I could at least say a few words to you, to thank you (…) to get yours and mom’s blessing, which I desperately desired, to hear a good word from you. Unfortunately, they wouldn’t allow us to have even that.”

He got to see his beloved son, with whom he spent only a few months after he was born (Andrzej was born in the beginning of 1947), only after three years. In October, 1950, when Łukasz Ciepliński was sentenced to death, his wife Jadwiga raised little Andrzej high in the court room so they could look at each other one last time.

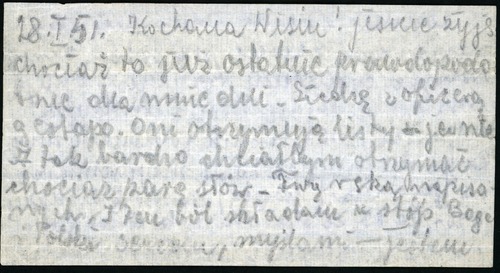

For Łukasz Ciepliński, this separation from his loved ones was one of the worst things he experienced in the communist prisons. He tried not to lose hope, and his only way of communicating with his family were hidden messages. The tragic circumstances of how he wrote them and, first and foremost, the wisdom and kindness of their author, striking in their authenticity, are a unique testament to the generation of Poles born and raised in the Second Republic of Poland; to their love of God, Poland and their compatriots.

“Dear Wisia! I am still alive, although these are likely my final days. I am jailed with an officer of the Gestapo. They receive letters, I don’t. And I would like to receive just a few words written by your hand. I offer this pain to God and Poland. (…)” - a secret message from Łukasz Ciepliński to his wife, January 28, 1951. From the archives of the Institute of National Remembrance

![“Little Andrzej! Love God and be a devoted Catholic. Always try to learn His Will, welcome it as the truth and implement it in your life. Love Poland and always have Her interests at heart. She must regain her rightful place in the world and give happiness to all her citizens. Love your mother and listen to what she says, she is your guardian angel (…) [Be good to her for me and for you.] (…)” - a secret message from Łukasz Ciepliński to his son, January 7, 1951. From the archives of IPN](/dokumenty/zalaczniki/166/mini/166-173302_m.jpg)

“Little Andrzej! Love God and be a devoted Catholic. Always try to learn His Will, welcome it as the truth and implement it in your life. Love Poland and always have Her interests at heart. She must regain her rightful place in the world and give happiness to all her citizens. Love your mother and listen to what she says, she is your guardian angel (…) [Be good to her for me and for you.] (…)” - a secret message from Łukasz Ciepliński to his son, January 7, 1951. From the archives of IPN

The archives of the Institute of National Remembrance hold the largest, currently known collection of these original messages, of these incredibly special artefacts of Polish history. When referring to them, Andrzej Ciepliński’s wife said that “the touch of this paper sent us to a completely different reality”. She added that it was “a hibernation of something almost holy.”

In his messages, Łukasz Ciepliński expressed a deep belief that even though he had lost his own fight, a new, good Poland would rise from the Polish victims such as him:

“In the coming days I am to be murdered by the communists for realising ideals which I’m passing on to you in my will. (…) In this heavy hour of my life, to know that my sacrifice will not go to vain, that my unfulfilled dreams and goals will not be shut down by an unknown grave, but that you will continue to realise them, fills me up with great joy (…)”

The uniqueness of Łukasz Ciepliński’s message is its unchanging relevance. The advice he gave to his son could also be the advice of any modern father to his children:

“You need to shape your mind, learn as much information as you can. Study hard. Leave for studies abroad (America, England, the Netherlands or Belgium). There, try to learn the current challenges of the scientific, economic, social, cultural and political life. Remember, you need to come back to your country with positive and factual information. Accept what is noble and grand, reject what is shallow and wicked.”

Back then, Łukasz Ciepliński had no way of knowing that the lives of his wife and son, after March 1, 1951, would be the never-ending string of tragedy sponsored by the communist regime. They experienced various kinds of humiliation, harassment and poverty. The name “Ciepliński” ended job interviews and was the reason for bullying in school. Without the help of their family, friends and other kind people, they would never survive financially. They could only earn some extra money — Andrzej with photography and Jadwiga by teaching piano or making sweaters. Meanwhile, the life of Aleksander Warecki in Warsaw looked completely different.

Despite such difficult hardships, Jadwiga Cieplińska kept saying:

“The truth will defend itself and Łukasz will be considered a hero. But I don’t want to live to see that happen, because that would be too much for me.”

And that is exactly what happened. She died before her husband’s name was cleared by the courts in 1992. The question remains whether the truth indeed defends itself. Perhaps the words of “Pług” which he said thinking of his son in the jail cell of the Rakowiecka prison are adequate here, and are also a lesson to us:

“(…) Tell him many stories about the actions of the Home Army and the Freedom and Independence Association, so he would be strongly tied to our values, which he should continue to uphold and fight for. (…)”

* * *

When he turned only 37, Łukasz Ciepliński had all the right in the world to write the following in one of his messages:

“I feel like a man who fulfilled his duties well.”

Poland, by slowly but surely bringing back the memory of Łukasz Ciepliński and honouring his memory, cannot yet say that it fulfilled all its duties towards him. Despite the enormous search efforts of the Institute of National Remembrance; despite the incredible efforts of countless volunteers helping in the search of the “Łączka” part of the Powązki Cemetery, we still do not know where “Pług” and his six colleagues from the 4th General Board of the Freedom and Independence Association are buried. We still do not know whether those murdered on March 1, 1951, the indomitable soldiers of the Polish freedom, will ever get their “unknown graves” found and receive a proper, Christian burial, appropriate for such esteemed heroes of Poland.