We know the fates of many foreign pilots who took part in the aforementioned war among the ranks of the Polish Army. The most famous Europeans among them were: Italian Captain Pilot Camillo Perini; Austrian-German Second Lieutenant Franz Peter; Czech Sergeant Pilot Josef Cagašek and Belgian Second Lieutenant Observer Robert Vanderauvera. The French definitely outnumbered the Italians, Germans, Belgians and Czechs. Some of the more famous among them were Captain Pilot Fernand Bonneton and, first and foremost, Second Lieutenant Pilot Claude Haegelen.

However, it was not only citizens of the Old Continent who fought for Poland. There was a peculiar group of American citizens of Polish descent, including Second Lieutenant Observer Włodzimierz Rice, Sergeant Pilot Piotr Toluściak and Second Lieutenant Observer Józef Jędrczak.

Budyonny versus King Kong

Without a shadow of doubt, the US citizens gained more fame than anyone else since they had little to do with the Polish culture, but they decided to fight for Poland’s borders anyway. The group was strictly connected to the figure of Captain Pilot Merian C. Cooper. In Spring, 1919, he was in Lviv, where he proposed to create a fighter squadron consisting of American volunteers. The idea came to the liking of the Polish commander in Eastern Galitia, General Lieutenant Tadeusz Rozwadowski. As advised by Rozwadowski, Cooper also got the initial agreement from Chief of State Józef Piłsudski.

Cooper wanted to return the favour to Poland for the great contributions of Tadeusz Kościuszko and Kazimierz Pułaski in the American War of Independence. He flew as a pilot of the 20th Air Squadron on the western front of the First World War. On September 26th, 1918, he was shot down and imprisoned by the Germans. But his fate became even more interesting when he came back from Poland — he ended up in the American film industry; he became a producer and film director. He also appeared on the silver screen, i.e. as one of the pilots fighting against the great ape in the film “King Kong”. During the Second World War he served, among others, as the chief of staff of the Fifth Air Force.

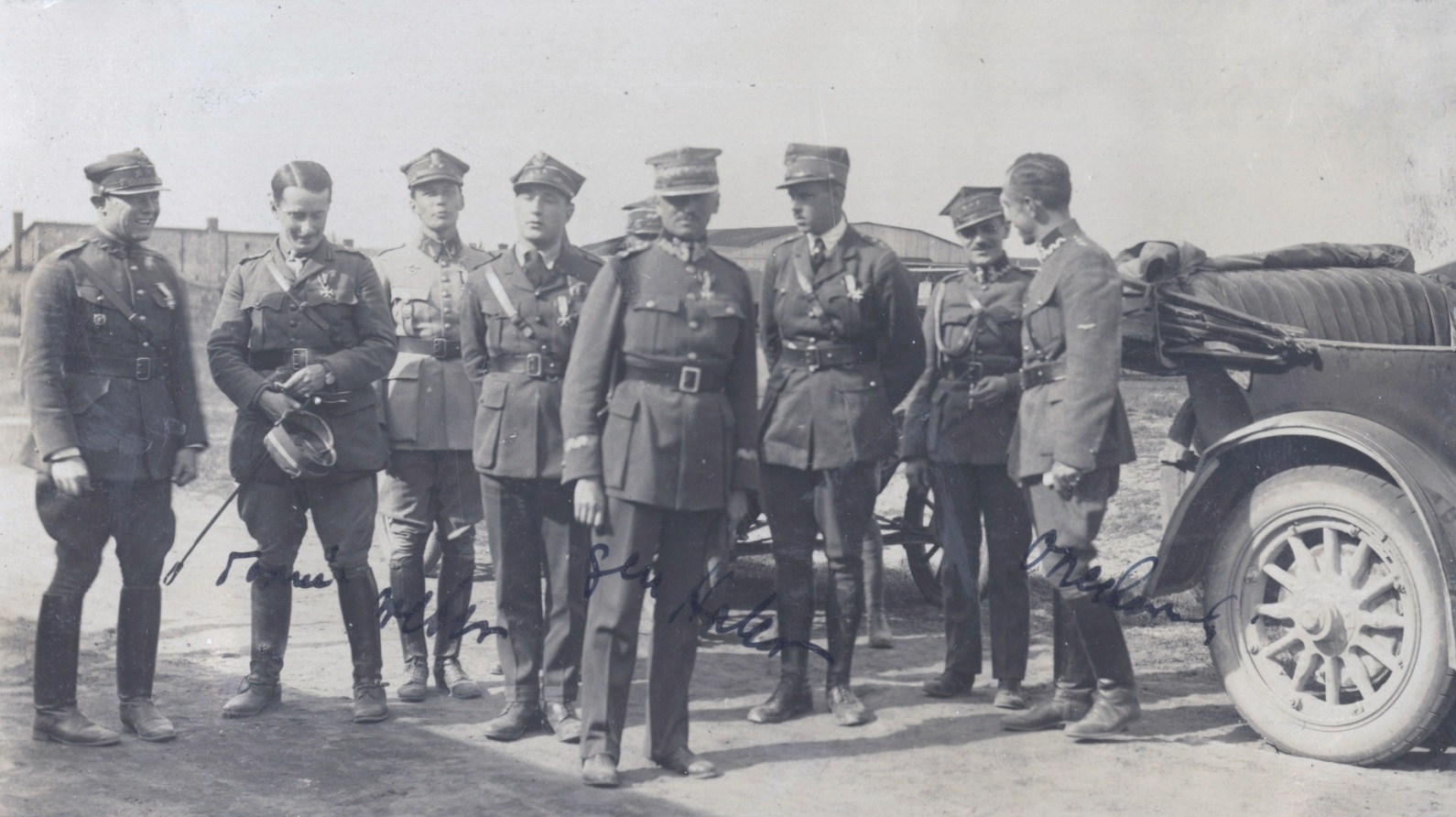

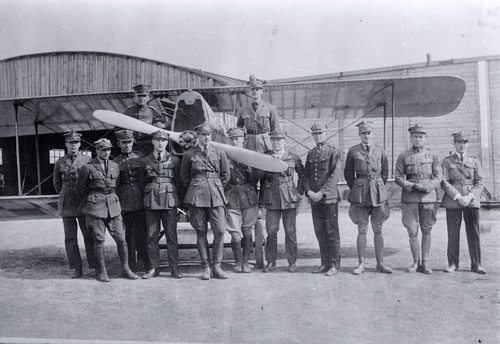

Lviv airmen accompanied by Entente officers. Signatures on the top point to Lieutenant Pilot Stefan Stec (on the right) and Lieutenant Observer Kazimierz Kubala. The signatures on the bottom list (from the right): Lieutenant Observer Tadeusz Wereszczyński and Lieutenant Observer Julian Pawłowski (most likely). The last signature is illegible. Steca is seen offering a cigarette to American Captain Pilot Merian C. Cooper. Lviv, spring of 1919. Photo from the Polish Air Force Museum in Cracow

Cooper’s first recruit was Major Pilot Cedric E. Faunt le Roy, the former pilot of the American Expedition Corps in France, as well as of the 94th Air Squadron. The Polish Military Purchasing Commission went into partnership with him after the First World War. The American was to give evaluations of planes before they were purchased by the Polish government. However, Cooper’s concept was more enticing for Faunt le Roy.

Cooper and Faunt le Roy set up something of a recruitment office in Café de la Paix in Paris. Next few American pilots went through these “cafe interviews”: Lieutenant Pilot George M. Crawford; Lieutenant Pilot Kenneth O. Shrewsbury; Captain Pilot Edward C. Corsi; Lieutenant Pilot Carl H. Clark; Lieutenant Pilot Edwin L. Noble and Captain Observer Arthur H. Kelly.

Rail transport of the Tadeusz Kościuszko 7th Air Escadrille. Ansaldo A.1 Balilla, serial no. 16717, is in the forefront. The Balillas replenished the squadron after the winter equipment losses. An Oeffag D.III with side number 8 is seen in the background. Captain Pilot Edward C. Corsi usually flew on that aircraft. Photo from the Polish Air Force Museum in Cracow

Corsi volunteered to the French army before the United States joined the war, he flew in the SPA 77th Squadron and was injured during an attack on an observation balloon. Crawford was Cooper’s colleague from the 20th Air Squadron; Shrewsbury transported planes from England to France before the end of the First World War. Kelly served in the 96th Air Squadron. Noble was also a veteran of American air force, while Clark had served in the British air force.

Soldiers of the good cause

The American officers signed six-month contracts with the Polish Army. They got the same equipment, privileges and duties as the Polish officers of analogical ranks. On September 16th, 1919, they began their journey to Poland as the crew of a sanitary train. Exactly one week later, they crossed the Polish-German border.

In October, two more pilots joined the group: Lieutenant Pilot Elliot W. Chess and Lieutenant Pilot Edmund P. Graves. They were both veterans of the British air force, but Graves was late for the First World War. Chess took part in combat flights in France and later became famous for coming up with the Kościuszko emblem, which he drew on the restaurant menu of the George hotel in Lviv.

On October 14th, the Americans showed up at Józef Piłsduski’s doorstep. They were received rather coldly. The Chief of State compared his guests to mercenaries. He did not oppose their service, but he said the famous words Show me what you can do!

The volunteers from beyond the ocean joined the 3rd Division 7th Oeffag Fighter Squadron. On October 18th, Faunt le Roy took the command of the squadron, which later took the name of Tadeusz Kościuszko. Several Polish pilots remained in the unit.

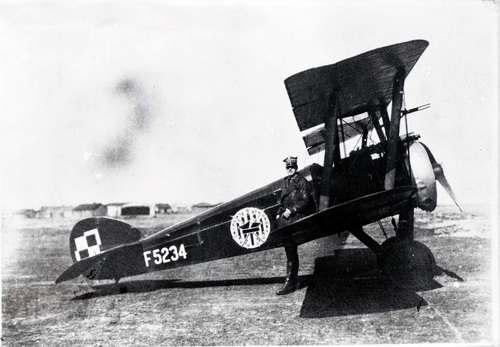

Lieutenant Pilot Kenneth M. Murray next to the Sopwith F.1 Camel fighter (British no. F5234), which made the journey with him to Poland. Camel did not take part in combat flights before the armistice, but Murray completed several tasks on the frontline. Photo from the Polish Air Force Museum in Cracow

The Polish-American squadron was separated into two platoons. The first one with red colours on the Oeffags’ noses, while the other one with blue. They were commanded by Cooper and Corsi respectively. There was also an idea to create the Kazimierz Pułaski Squadron. However, it was rejected due to concerns that this could take away from the supplies of other Polish air units. So as not to curb the enthusiasm of the Americans, Cooper’s platoon received the name Pułaski Hunting Unit of the Kościuszko Polish-American Squadron.

On November 22, the volunteers suffered their first loss. During the air manoeuvres, the wings of Graves’ Oeffag tore off. The pilot jumped out with his parachute, but the altitude was low and the jump ended with his death. His spot was filled by Lieutenant Pilot Harmon Ch. Rorison, the test pilot (and later full-fledged pilot) of the 22nd Air Squadron, who became famous for shooting down three German planes in a single day.

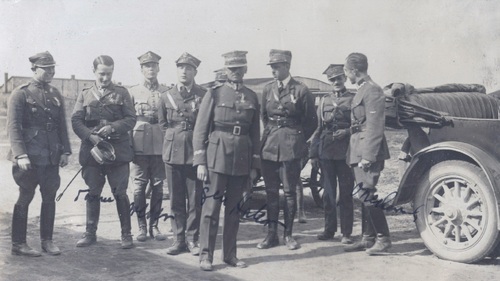

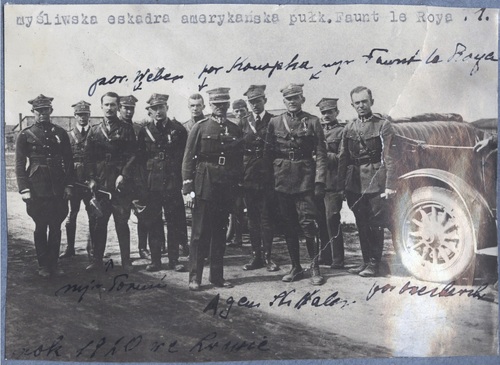

American and Polish officers accompanied by General Major Haller (in the cap with the General’s strip). The photograph was taken in October, 1920, after Gen. Haller awarded the pilots of the 3rd Air Squadron with Silver Crosses of the Fifth Class of the War Order of Virtuti Militari. Photo from the Polish Air Force Museum in Cracow

American and Polish officers accompanied by General Major Haller (in the cap with the General’s strip). The photograph was taken in October, 1920, after Gen. Haller awarded the pilots of the 3rd Air Squadron with Silver Crosses of the Fifth Class of the War Order of Virtuti Militari. Photo from the Polish Air Force Museum in Cracow

The Polish-American escadrille, boosted by Rorison, made its mark during the Kyiv offensive and later during the clashes against the 1st Cavalry Army of Semyon Budyonny. Nevertheless, it suffered some losses during the several, intense months of fighting. Noble was seriously wounded during the Kyiv operation. Cooper and Kelly were both shot down in July. The former was taken prisoner, the latter died. Shrewsbury, Rorison and Clark did not extend their contracts. Then, after the intervention of Faunt le Roy, six more airmen were recruited in the United States. Some of them made it in time to fly on combat missions during the Polish-Bolshevik war. Several more volunteers began their journey, but failed to reach their destination before the armistice. Next 30 volunteered too late to even start travelling to Poland.

The fate of the 7th Air Escadrille in 1920 is truly an interesting episode of the Polish-American brotherhood of arms. Yet the service of American volunteers in Poland was not only symbolic, but also practical. The Polish Air Force had a serious lack of personnel. The participation of Americans, but also other foreigners, contributed positively to the combat capabilities of the Air Force during the armed shaping of the borders of the Second Republic of Poland.

Officers of the 7th Air Escadrille standing in front of the Ansaldo A.1 Balilla. Standing from the left: Jerzy Weber; Antoni Poznański; Zbigniew Orzechowski; Edward C. Corsi; George M. Crawford; John C. Speaks; Elliot W. Chess; Earl Evans; John I. Maitland; Aleksander Seńkowski; Thomas Garlick. On the right wheel: Władysław Konopka. On the left wheel: Kenneth M. Murray. The photograph was taken after the end of the Polish-Bolshevik war. Photo from the Polish Air Force Museum in Cracow